|

Over fifteen hundred pages of supporting documents have been submitted by six cities vying to become the new home of the National Championship Air Races (NCAR) after responding to a request for proposal distributed by the Reno Air Racing Association (RARA) earlier this year. RARA is looking for a new venue for the event after announcing its departure from Reno following the final race in September. The world-renowned event has contributed over $100 million annually in economic impact to the region, while also establishing itself as the global standard for air racing. The National Championship Air Races is the only event in the world to feature seven classes of exciting air racing action in one incredible venue. Six closed-course pylon contests and the immensely popular and entertaining STOL Drag combine to create a motorsport experience like no other. Seeing the interest to host the National Championship Air Races at each of these unique venues gives me great hope for the future of air racing,” said Fred Telling, CEO and chairman of the board for the Reno Air Racing Association. “We’re looking for our next home, somewhere we can celebrate many more anniversaries, so we’ve assembled an expert committee that is putting an extreme amount of care and diligence into choosing our next location.” The bidders that responded to the request for proposals include:

The committee researching the bid submissions is made up of RARA personnel from all areas, including operations, safety, security, business development, and more. The race classes are also represented in the group and will continue to be an integral part of the selection process. At this point, the selection committee is thoroughly vetting the different proposals and will conduct site visits later this year. There are numerous factors to consider, but a few of the critical requirements for the event include considerable open land available for the racecourses, suitable runways, ramp, and hangar space, administrative and security facilities, as well as proximity to hotels, commercial airports, and restaurants. “We only want to go through this process once and because of that, we’re going to make sure our next location is the best fit for the future of the air races,” said Terry Matter, board member and chairman of the selection committee. “Each of the bidders’ proposals were thoroughly prepared and completely addressed the RARA RFP requirements. We are so grateful for their initial attendance at the bidders’ conferences and at NCAR in September, and for the time and effort each one of them put into their proposal preparation. It is very exciting to know that our new home will be in one of these great cities. Soon our Site Selection Committee will visit these locations to further evaluate their ability to be the future host of the National Championship Air Races.”

A final decision is expected to be announced early next year as the organization prepares for a final air show in Reno in 2024 before moving to the new location in 2025. For more information and ways to support the organization, visit www.airrace.org. About the National Championship Air Races The National Championship Air Races are held every September just north of Reno by the Reno Air Racing Association, a 501(c)(3). The event has become an institution for Northern Nevada and aviation enthusiasts from around the world with seven racing classes, a large display of static aircraft and several military and civilian flight demonstrations. Independent economic impact studies show that the event generates as much as $100 million annually for the local economy. For more information on the National Championship Air Races, visit AirRace.org.

0 Comments

Daher has recently surpassed 500 deliveries of the TBM 900 series single turboprop. The milestone aircraft was handed over to a U.S. customer just ahead of NBAA-BACE 2023.

The TBM 900 was first introduced in 2014, following the production of 324 TBM 700s and 338 TBM 850s. The first of these aircraft—the TBM 700 initially developed jointly by Socata (formerly Morane-Saulnier) and Mooney—made its first flight on July 14, 1988. The more powerful TBM 850 first flew in 2005, shortly before Daher took a 70 percent stake in what had become Eads-Socata. It subsequently acquired the remaining 30 percent from Eads. Notably, the TBM 900 ushered in winglets and a Hartzell five-blade scimitar propeller, among other improvements to the turboprop. The family evolved through the 930 (2016, a higher-end version with Garmin G3000 touchscreen cockpit), the 910 (2018, similar to the 900 with G1000 NXi avionics), and the 940 (2019, a derivative of the 930 with autothrottle and, from 2020, the Homesafe emergency autoland system). Today the flagship is the TBM 960, which is powered by a PT6E-66XT turboprop with dual-channel digital electronic propeller and engine control. Following its unveiling in 2022, the TBM 960 has been a strong seller. Deliveries had reached 92 at the end of September, and more than 100 aircraft are on order. That equates to more than two years of production. BREAKING Ural Airlines A320 will attempt a take-off from the field where it landed, ran out of fuel10/5/2023 Ural Airlines A320 (reg. RA-73805), that will attempt a take-off from its current location, after the aircraft ran out of fuel and landed in a grass field on September 12th.

The airline confirmed the decision to make the Airbus A320 to takeoff form its current location The airline is awaiting the delivery of lifts to carry out landing gear testing. The plan also includes dismantling the seats to make the aircraft lighter. A potential solution to carbon-free flying is inching closer to reality. Since the start of this year, small planes equipped with hydrogen fuel cells have made their first test flights over the U.S. West Coast and the English countryside. The aviation startups ZeroAvia and Universal Hydrogen now claim their novel aircraft will be ready to start flying commercially as early as 2025. A new analysis suggests that, if the technology can scale, it could sharply reduce greenhouse gas emissions for certain planes — and potentially lay the groundwork for decarbonizing broader swaths of the global aviation market. Retrofitting a propeller plane with fuel cells and liquid-hydrogen tanks would result in a nearly 90 percent reduction in life-cycle emissions, compared to the original aircraft, according to the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT), a nonprofit think tank. That’s assuming the hydrogen is made using only renewable electricity —not with fossil fuels, the way the vast majority of hydrogen is produced today. Fuel cells work somewhat like batteries. On planes, hydrogen flows into the fuel-cell system and spurs an electrochemical reaction that produces electricity; this in turn drives electric motors and spins propellers. But barring a technological breakthrough, fuel cells can’t produce enough power to carry the large, long-distance aircraft that are responsible for the bulk of aviation’s carbon dioxide emissions. Instead, the tech will likely be restricted to short-haul, turboprop airliners that can seat roughly 50 to 60 passengers and fly just a few hundred miles, such as the distance from New York City to Washington, D.C. Today’s turboprops represent about 1 percent of global passenger traffic. Still, experts say fuel cells could help pave the way for larger and more powerful hydrogen models, including potentially jets with combustion engines that burn liquid hydrogen. Airbus and Boeing, the world’s top two aircraft makers, are both developing hydrogen technologies as the industry faces growing public pressure to address climate change. “The introduction of the fuel-cell aircraft will be the testing ground for just generally using hydrogen in aviation,” Jayant Mukhopadhaya, aerospace engineer and a Berlin-based researcher for ICCT, told Canary Media. “How will it work at airports, how is the refueling going to happen, how does hydrogen get delivered, what safety concerns you’re going to have — all of those bits and pieces.” Why hydrogen is gaining favor Around the world, commercial air travel accounts for over 2 percent of energy-related CO2 emissions, according to the International Energy Agency. That number is set to soar in the coming years as more oil-burning planes and more passengers hit the skies. In the near term, airlines and plane manufacturers are working to curb emissions by designing more fuel-efficient engines, electrifying ground operations and increasing their use of “sustainable aviation fuel” made from used cooking oil, forestry residues, carbon dioxide and other feedstocks. Last year, alternative fuels accounted for less than 0.1 percent of the total jet fuel used by major U.S. airlines. Although plant- and waste-based fuels can be cleaner to produce than petroleum-based fuel, they still emit carbon dioxide when burned in engines. Hydrogen does not — that’s why airlines and manufacturers are joining efforts to develop H2-powered aircraft. Fuel cells in particular don’t generate harmful nitrogen oxides or fine particulate matter, since they don’t burn fuel. A retrofitted fuel-cell aircraft would emit about one-third less CO2 over its lifetime than an aircraft burning “e-kerosene,” a type of sustainable aviation fuel made from electricity, water and carbon dioxide, according to the ICCT analysis. Hydrogen, especially of the “green” variety, costs significantly more to make and buy than conventional kerosene. However, because fuel-cell systems are far more energy-efficient than engines, aircraft don’t need to use as much fuel to fly. If green-hydrogen production ramps up and fuel-cell aircraft catch on, it could be cheaper to refuel with H2 than fossil jet fuel in the United States in 2050, the ICCT said in a white paper published on Wednesday.

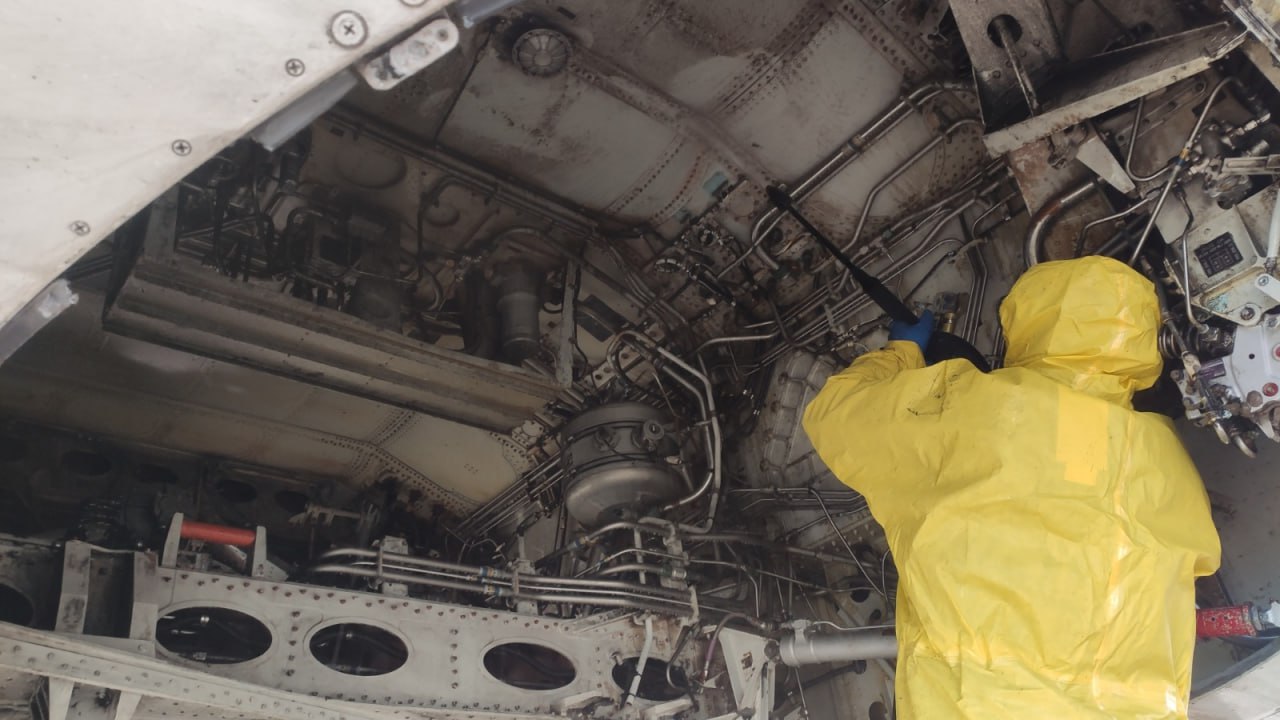

“The most surprising part was the [energy] efficiency impacting the price of fuel,” Mukhopadhaya said. “That was something we weren’t expecting.” Hydrogen aviation takes first flightsZeroAvia and Universal Hydrogen, both headquartered in California, have spent the first half of 2023 testing and demonstrating some of the world’s first hydrogen fuel-cell aircraft. In January, ZeroAvia first launched its 19-seat prototype plane at Cotswold Airport, a private airfield near the English village of Kemble surrounded by farms and grazing sheep. The blue-and-white Dornier 228 has now flown 10 times, hitting key milestones and enabling the company to begin the next phase of flight testing. ZeroAvia, which has raised over $140 million from investors including United Airlines and American Airlines, retrofitted one side of its twin-engine turboprop with fuel cells and batteries, which can reach a maximum power of 600 kilowatts. The other side kept its oil-burning jet engine. Over the course of six months, the aircraft reached a maximum speed of 150 knots, flew to a height of 5,000 feet and performed an endurance test for 23 minutes. “There was no malfunction of the fuel cell during the flight-test campaign,” Gabriele Teofili, ZeroAvia’s head of aircraft integration and testing, said on a recent call from the airport’s hangar, tilting his laptop to show the prototype parked behind him. Teofili said the company successfully demonstrated to the U.K. Civil Aviation Authority that the hydrogen-electric system behaved as expected — and that the aircraft has enough range to fly to another nearby airport. ZeroAvia is now preparing to begin its first cross-country flights in England before the end of this year. It’s also working to retrofit a second regional turboprop in Washington state, in partnership with Alaska Airlines. “The idea is to demonstrate that it’s not only possible, but it’s safe, it’s reliable, and it’s profitable,” Teofili said of the hydrogen aircraft. He noted that ZeroAvia plans to shed the batteries and engines that it’s using during testing to deliver a final aircraft powered only by a 1.8-megawatt fuel cell. The company claims it’s on track for commercial operations in 2025, starting with a nine- to 19-seat aircraft with a 300-mile range. Meanwhile, Universal Hydrogen says it’s making progress on an even bigger retrofitted turboprop. The company has raised at least $82.5 million from investors such as GE Aviation, American Airlines and the venture capital arms of Airbus, JetBlue and Toyota. In March, the Los Angeles–based startup launched its first test flight from a small airport near Moses Lake, Washington. Its 40-passenger Dash 8 prototype has one original engine, plus a 1.2-megawatt fuel cell and 800-kilowatt electric motor, with no batteries. Mark Cousin, Universal Hydrogen’s CTO, said the aircraft has flown nine total times, including a series of trips from Washington down to Mojave, California, where the plane now resides. The prototype climbed up to 10,000 feet high, hit speeds of 170 knots, and operated for more than an hour in flight. The company is continuing to test key elements of the hydrogen powertrain, including the cooling system that keeps the fuel cell from overheating — a challenge that can limit the technology’s performance and range. Universal Hydrogen is also preparing to ground test a 2 MW powertrain on an ATR 72 turboprop, which could begin flight-testing in 2025, Cousin said. The company aims to enter a hydrogen-fueled aircraft into passenger service later that year or in early 2026. Both ZeroAvia and Universal Hydrogen are using hydrogen in its gaseous form to power fuel cells during flight testing, though the companies plan to use liquid hydrogen eventually. The fuel is less widely available today, but it packs more energy on a volume basis than gaseous H2 and can be stored in fewer, lighter tanks on the aircraft. Along with retrofit conversion kits, Universal Hydrogen is also developing liquid-hydrogen storage capsules. The idea is to collect hydrogen from electrolyzer plants, which use water and renewable electricity to produce “green” hydrogen — and today remain few and far between. Trucks or trains would then transport the capsules to airports. Cousin said the company’s ultimate goal is to convince airlines and major airplane manufacturers that it’s possible to develop the necessary infrastructure for powering larger hydrogen-burning aircraft. Airbus, for instance, is building a demonstration engine to test hydrogen propulsion in one of its A380 superjumbo jets. “The real objective is to demonstrate not only that we can fly a [turboprop] on hydrogen, but also to demonstrate that hydrogen propulsion…is a viable solution for short- to medium-range operations,” he said. Two passengers on an Air Canada flight were reportedly escorted off an airplane for refusing to sit in wet, vomit-covered seats. Susan Benson was fellow passenger on the same Aug. 26 flight from Seattle to Montreal sitting near the vomit. She shared the incident in a now-viral Facebook post to hold the airline accountable because she felt it was unfair to the passengers. "There was a bit of a foul smell but we didn’t know at first what the problem was,” Benson wrote in the post. “Apparently, on the previous flight someone had vomited in that area. Air Canada attempted a quick cleanup before boarding but clearly wasn’t able to do a thorough clean.” According to Benson, the seatbelt and seat were still visibly wet and there was vomit residue around the seats. The smell of vomit mixed with the scent of perfume and coffee grinds, which were put in the seat pouch to mask the smell. The passengers flagged down a flight attendant to tell her they couldn’t sit in those seats for the five-hour flight, calling the incident “unacceptable,” Benson told USA TODAY over the phone. “The passengers were clearly upset and clearly bothered,” Benson said. “They were not rude, not yelling, not belligerent. They were firm and just insistent that she couldn’t sit in that.” According to Benson, the flight attendants were “extremely apologetic” and said, “it was a miscommunication with the cleaning crew the night before and the seat didn’t get cleaned properly.” They also told the passengers there was nothing they could do because all the seats were full. After some back and forth, the passengers were given blankets, wipes and more vomit bags and settled in for the flight. Security came soon after and escorted the women off the flight. “Air Canada literally expects passage (sic) to sit in vomit or be escorted off the plane and placed on a no-fly list!” Benson wrote.

The flight ended up being 31 minutes delayed but made it to Montreal safely. Benson told USA TODAY that she posted details of the incident online to hold Air Canada accountable so “they would do something about it.” She feels as if the airline treated the passengers unfairly. Air Canada did not respond immediately to USA TODAY’s request for comment but shared a statement with Insider saying, “We are reviewing this serious matter internally and have followed up with the customers directly as our operating procedures were not followed correctly in this instance. This includes apologizing to these customers, as they clearly did not receive the standard of care to which they were entitled and addressing their concerns.” “I really hope they actually do something and not just say they do to keep the peace,” Benson said. “(The passengers) weren’t unreasonable at all in my opinion.” No panic and immediate wind speed and direction call outs. That ground crew has been around the block. A Boeing 737-8 MAX straight from the factory was flying when the pilot declared an emergency, telling the ATC tower that they had no autopilot trim and no electrical trim system and had to trim the aircraft manually. Southwest Airlines Boeing, registration N8844Q, was flying from Phoenix Sky Harbor International Airport (PHX) to William P. Hobby Airport (HOU). The pilot reported a trim and autopilot issue and declared an emergency, requesting a return to the airport. The crew requested to level off at 11,000 feet and began running checklists. The pilot and ATC tower calmly communicated the situation and were able to navigate back to the airport safely. The plane returned to Phoenix about 23 minutes after departure and the pilot was able to navigate back to the airport, trimming manually, and safely land without any injury to the 164 passengers on board or damage to the aircraft. The plane had arrived in Phoenix on its delivery flight from Boeing Field the day before and successfully entered service roughly 14 hours later, according to the Aviation Herald. Trimming an aircraft means adjusting the aerodynamic forces on the control surfaces, allowing the pilot to maintain the set attitude without using any control input. RENO, Nathan Finneman Nev. — The National Championship Air Races will be leaving Reno after September's event after nearly 60 years in northern Nevada. On the air race's website, organizers said that the final race will be held September 13-17 at the Reno-Stead Airport. A letter sent to supporters and fans said the Reno Tahoe Airport Authority made the decision to sunset the event citing the region's significant growth. The airport authority said there's concerns surrounding economic conditions, rapid area development, public safety and the impact on the Reno-Stead Airport and its surrounding areas. During the event in 2022, a pilot from California was killed when his jet went down during the championship round of the races. In September 2011, more than 60 people were hurt and 11 people were killed when a racing plane nosedived into the grandstands. The tragedy marked the third-deadliest airshow disaster in U.S. history. Air racing enthusiasts are inviting the community and race fans from all over the world to join them in sending the Reno Air Races off in style one last time.

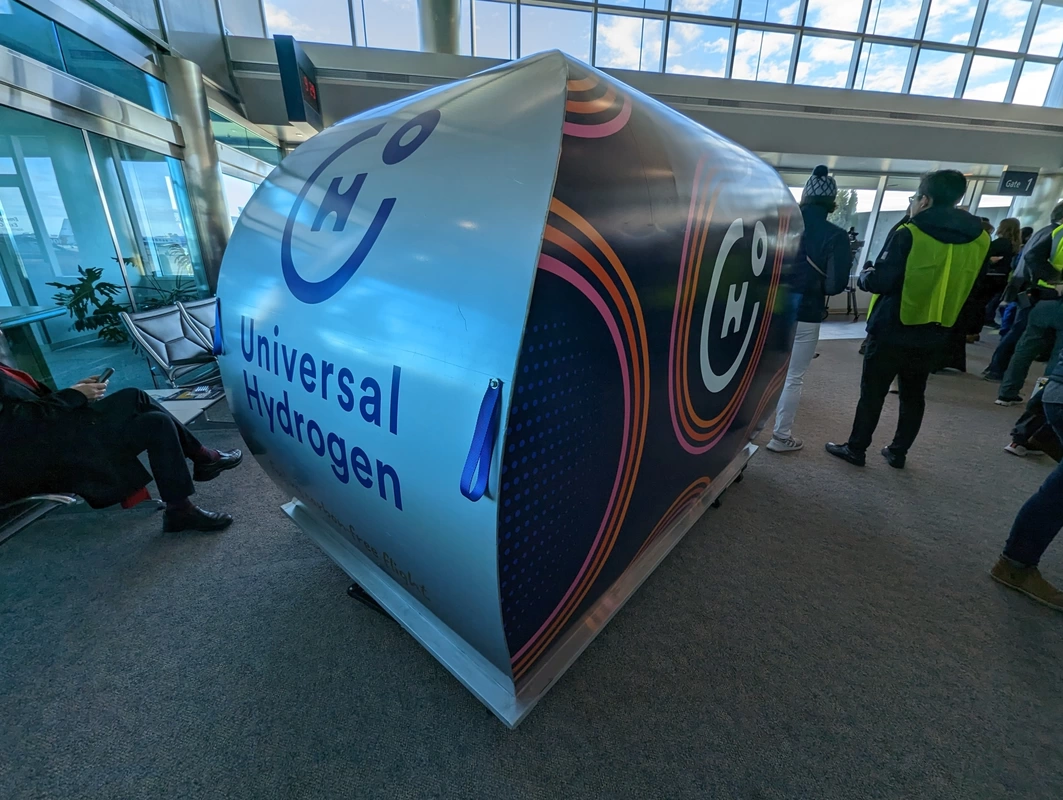

The organization will continue to discuss the future of the races but are forever grateful for the decades spent at the Reno-Stead Airport and their partnership with the Reno Tahoe Airport Authority. The final event is set to return more than 150 planes and pilots as well as several 'hands-on' displays and experiences. Hydrogen-branded plane, equipped with the largest hydrogen fuel cell ever to power an aircraft, made its maiden test flight in eastern Washington, co-founder and CEO Paul Eremenko declared the moment the dawn of a “new golden age of aviation.” The 15-minute test flight of a modified Dash-8 aircraft was short, but it showed that hydrogen could be viable as a fuel for short-hop passenger aircraft. That is, if Universal Hydrogen — and others in the emerging world of hydrogen flight — can make the technical and regulatory progress needed to make it a mainstream product. Dash-8s, a staple at regional airports, usually transport up to 50 passengers on short hops. The Dash-8 used in Thursday’s test flight from the Grant County International Airport in Moses Lake had decidedly different cargo. The Universal Hydrogen test plane, nicknamed Lightning McClean, had just two pilots, an engineer and a lot of tech onboard, including an electric motor and hydrogen fuel cell supplied by two other startups. The stripped-down interior contained two racks of electronics and sensors, and two large hydrogen tanks with 30 kg of fuel. Beneath the plane’s right wing, an electric motor from magniX was being driven by the new hydrogen fuel cell from Plug Power. This system turns hydrogen into electricity and water — an emission-free powerplant that Eremenko believes represents the future of aviation. The fuel cell operated throughout the flight, generating up to 800kW of power and producing nothing but water vapor and smiles on the faces of a crowd of Universal Hydrogen engineers and investors. “We think it’s a pretty monumental accomplishment,” Eremenko said. “It keeps us on track to have probably the first certified hydrogen airplane in passenger service.” Aviation currently contributes about 2.5% of global carbon emissions, and is forecast to grow by 4% annually. The test flight, which was a success, doesn’t mean entirely zero-carbon aviation is just around the corner. Beneath the Dash-8’s other wing ran a standard Pratt and Whitney turboprop engine (notice the difference in the photo above), with about twice as much power as the fuel-cell side. That redundancy helped smooth a path with the FAA, which issued an experimental special airworthiness certificate for the Dash-8 tests in early February. One of the test pilots, Michael Bockler, told TechCrunch that the aircraft “flew like a normal Dash-8, with just a slight yaw.” He noted that at one point, in level flight, the plane was flying almost entirely on fuel cell power, with the turboprop engine throttled down. “Until both motors are driven by hydrogen, it’s still just a show,” said a senior engineer consulting to the sustainable aviation industry. “But I don’t want to scoff at it because we need these stepping stones to learn.” Part of the problem with today’s fuel cells is that they can be tricky to cool. Jet engines run much hotter, but expel most of that heat through their exhausts. Because fuel cells use an electrochemical reaction rather than simply burning hydrogen, the waste heat has to be removed through a system of heat exchangers and vents. ZeroAvia, another startup developing hydrogen fuel cells for aviation, crashed its first flying prototype in 2021 after turning off its fuel cell mid-air to allow it to cool, and was then unable to restart it. ZeroAvia has since taken to the air again with a hybrid hydrogen/fossil fuel set-up similar to Universal Hydrogen’s, although on a smaller twin-engine aircraft. Mark Cousin, Universal Hydrogen’s CTO, told TechCrunch that its fuel cell could run all day without overheating, thanks to its large air ducts. Another issue for fuel cell aircraft is storing the hydrogen needed to fly. Even in its densest, super-cooled liquid form, hydrogen contains only about a quarter the energy of a similar volume of jet fuel. Wing tanks are not large enough for any but the shortest flights, and so the fuel has to be stored within the fuselage. Today’s 15-minute flight used about 16kg of gaseous hydrogen — half the amount stored in two motorbike-sized tanks within the passenger compartment. Universal Hydrogen plans to convert its test aircraft to run on liquid hydrogen later this year. Eremenko co-founded Universal Hydrogen in 2020, and the company raised $20.5 million in a 2021 Series A funding round led by Playground Global. Funding to date is approaching $100 million, including investments from Airbus, General Electric, American Airlines, JetBlue and Toyota. The company is headquartered just up the road from SpaceX in Hawthorne, California, with an engineering facility in Toulouse, France.

Universal Hydrogen will now conduct further tests at Moses Lake. The company will work on additional software development, and eventually convert the plane to use liquid hydrogen. Early next year, the aircraft will likely be retired — with the fuel cell heading to the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC. Universal Hydrogen hopes to start shipping fuel cell conversion kits for regional aircraft like the Dash-8 as soon as 2025. The company already has nearly 250 retrofit orders valued at more than $1 billion from 16 customers, including Air New Zealand. John Thomas, CEO of Connect Airlines, which plans to be the first U.S. carrier to use Universal Hydrogen’s technology, said the “partnership provides the fastest path to zero-emissions operation for the global airline industry.” Universal Hydrogen isn’t just producing the razors — it’s also selling the blades. Almost all the hydrogen used today is produced at the point of consumption. That’s not only because hydrogen leaks easily and can damage traditional steel containers, but mainly because in its most useful form — a compact liquid — it has to be kept at just 20 degrees above absolute zero, usually requiring expensive refrigeration. The liquid hydrogen used in the Moses Lake test came from a commercial “green hydrogen” gas supplier — meaning it was made using renewable energy. Only a tiny fraction of hydrogen produced today is made this way. If the hydrogen economy is really going to make a dent in the climate crisis, green hydrogen will have to become a lot easier — and cheaper — to produce, store and transport. Eremenko originally started Universal Hydrogen to design standardized hydrogen modules that could be hauled by standard semi-trucks and simply slotted into aircraft or other vehicles for immediate use. The current design can keep hydrogen liquid for up to 100 hours, and he has often likened them to the convenience of Nespresso units. Universal Hydrogen says it has over $2 billion in fuel service orders for the decade ahead. Prototype modules were demonstrated in December, and the company hopes to break ground later this year on a 630,000-square-foot manufacturing facility for them in Albuquerque, New Mexico. That nearly $400 million project is contingent on the success of a previously unreported $200+ million U.S. Department of Energy loan application. Eremenko says the application has passed the first phase of due diligence within the DOE. Some experts are skeptical that hydrogen will ever make a meaningful dent in aviation’s emissions. Bernard van Dijk, an aviation scientist at the Hydrogen Science Coalition, appreciates the simplicity of Universal Hydrogen’s modules, but notes that even NASA has trouble controlling hydrogen leaks with its rockets. “You still have to connect the canisters to the aircraft. How is that all going to be safe? Because if it leaks and somebody lights a match, that is a recipe for disaster,” he says. “I think they’re also underestimating the whole certification process for a new hydrogen powertrain.” Even when those obstacles are overcome, there is the problem of making enough green hydrogen using renewable electricity, at a price people will be prepared to play. “If you want to get all European flights on hydrogen, you’d need 89,000 large wind turbines to produce enough hydrogen,” says van Dijk. “They would cover an area about twice the size of the Netherlands.” But Eremenko remains convinced that Universal Hydrogen and its partners can make it work, with the help of a $3 per kilogram subsidy for green hydrogen in Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act. “Of all the things that keep me awake at night,” he says, “the cost and availability of green hydrogens is not one of them.” A Cuban pilot defected to the United States via Florida Friday after winging in on a single-engine Russian-made plane, airport authorities said. Around 11:30 am (1530 GMT), the pilot arrived aboard a Russian Antonov AN-2 single-engine plane at Dade-Collier Airport, located in the Everglades, officials said. "He said that he was defecting, and that he was from Sancti Spritus," a province in central Cuba, the same sources specified. Cuba is the only one-party Communist-ruled country in the Americas. CiberCuba media outlet, which was the first to report the news, identified the aviator as Ruben Martinez and said that he worked for the Cuban Air Services Company (ENSA). Agents from the United States Customs and Border Protection (CBP) arrived at the landing site to look into the case, airport sources said. Many Cubans have tried to reach the United States in recent months after leaving their country, hit by its worst economic crisis in three decades with shortages of food, medicine and fuel. Between October 2021 and August 2022, close to 200,000 Cubans were intercepted by US authorities, according to CBP, after entering through the border with Mexico or crossing by sea through the Florida Straits.

That is a dramatic increase over the same period last year, when the United States intercepted some 30,000 Cubans. Cubans are the only people who are eligible for immediate US asylum if they flee their homeland and reach United States soil. However, if they are intercepted at sea, they are returned home. Critics say the policy encourages Cubans to make dangerous bids to reach US soil in planes and makeshift boats. |

Send us an email at [email protected] if you want to support this site buying the original Division of Aero Patch, only available through this website!

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed