Ex-US fighter pilot accused of training Chinese military will be extradited to the United States1/18/2025 A former US Marine accused of training Chinese military pilots will be extradited to face charges in the United States, Australia’s Attorney General confirmed Monday, dealing a blow to supporters who have mounted a public campaign for his freedom. Daniel Duggan, a naturalized Australian, was arrested in the state of New South Wales in 2022 based on a 2017 US grand jury indictment that accuses him of training Chinese military pilots in violation of a US arms embargo. Duggan denies the charges, claiming that US officials knew about his activities and that he was only training civilian pilots as China’s aviation sector boomed. Attorney General Mark Dreyfus confirmed that Duggan “should be extradited to face prosecution for the offences of which he is accused.” “Mr Duggan was given the opportunity to provide representations as to why he should not be surrendered to the United States. In arriving at my decision, I took into consideration all material in front of me,” Dreyfus said in a statement Monday. His decision follows court approval for Duggan’s extradition by a magistrate in May. In a statement, the pilot’s wife, Saffrine Duggan, said she and their six children were “shocked and absolutely heartbroken by this callous and inhumane decision which has been delivered just before Christmas with no explanation or justification from the Government.” “We feel abandoned by the Australian Government and deeply disappointed that they have completely failed in their duty to protect an Australian family. We are now considering our options,” she said.

If convicted, Duggan faces a prison sentence of up to 65 years. Duggan has been in custody since his arrest in October 2022, just weeks after returning to his family in Australia from six years working in China. He was detained by Australian police acting on the request of US authorities. The 2017 indictment filed in the District of Columbia says that “as early as 2008,” Duggan received an email from the US State Department telling him he was required to register with the Directorate of Defense Trade Controls and apply for permission to train a foreign air force. Instead, it claims he conspired with others – including the Test Flying Academy of South Africa (TFASA) – to export defense services in violation of an arms embargo on China. In a statement to CNN in 2023, TFASA said it complies with the laws of every jurisdiction in which it operates. The statement said Duggan undertook one test-pilot contract for the company in South Africa between November and December 2012, and “never worked for TFASA on any of its training mandates in China.” Duggan moved to China in 2013 and renounced his US citizenship at the US embassy in Beijing in 2016, though it was backdated on a certificate to 2012 to reflect when he became an Australian citizen, according to his lawyers. In an 89-page submission filed to Dreyfus’ office in August, Duggan’s lawyers alleged the former US serviceman had become a political pawn during a time of heightened US-China tensions. It said that his case had been used to send a message to Western pilots that any dealings with China will not be tolerated by the US, or its allies. “The extradition request is a brutal response to US Sinophobia,” his lawyer Bernard Collaery wrote in a cover letter attached to the submission. “While scapegoating Daniel Duggan may please some, his extradition into a baying political environment and semi-lawless prison system may also constitute a profound moral and foreign policy failure by Australia,” he wrote. Duggan’s arrest two years ago came as the US, the United Kingdom and Australia formed a stronger security bond under AUKUS, a deal they signed in 2021 to join forces in the Pacific to counter an increasingly assertive China. Since then, the UK and Australia have tightened their laws surrounding former military personnel and their post-service activities.

0 Comments

The 2024 compromise defense bill won’t let the Air Force retire its T-1A Jayhawk trainers until the service’s new pilot training system is up and running and the Secretary of the Air Force certifies that retiring the jet won’t slow the pace of producing new pilots. The bill also might allow the Air Force to accept some T-7A advanced trainers built before a contract for them is actually in place. The 2024 National Defense Authorization Bill prohibits Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall from retiring any of the service’s aging T-1A Jayhawks until he certifies the “full, fleet-wide implementation” of the new Undergraduate Pilot Training curriculum, previously called UPT 2.5. Kendall also has to send Congress a written assessment of how the UPT curriculum will affect the completion rates of new pilot trainees, and whether the retirements affect the speed at which they complete their training. The Air Force had asked to retire 52 T-1As in the fiscal 2024 defense budget request. The jets have been used since the 1990s to train pilots on the tanker/transport track, but under the new UPT curriculum, the live-fly T-1 curriculum would be phased out in favor of all-simulator training. The service has said that the new UPT scheme will be more individualized and allow pilots to progress more at their own pace, thus reducing the number of washouts and working to erase the Air Force’s chronic pilot shortage, which has wavered between 1,500 and 2,000 pilots for a decade. Even before the 2024 defense bill got to Congress, some Republican members were lobbying the service to upgrade and retain the jets, which are at or beyond their planned service lives. In a February letter from some members of the Mississippi delegation—Sens. Roger Wicker and Cindy Hyde-Smith, as well as Reps. Michael Guest and Trent Kelly—the lawmakers voiced concern that if there’s a delay with shifting to high-fidelity simulation at the necessary scale, “the Air Force will lose any ability to effectively train pilots” in an aircraft comparable to what they’ll fly after graduation. Given “recent media reports of further delays in the T-7A program, the T-1A may be the best defense against unforeseen shortfalls that may adversely affect the pilot training pipeline,” the Mississippi lawmakers wrote. Columbus Air Force Base in Mississippi is one of the Air Force’s UPT bases. The Jayhawk is also flown at Laughlin and Randolph Air Force Bases in Texas; Vance Air Force Base in Oklahoma and at Naval Air Station Pensacola, Fla., where the Air Force jointly conducts some of its weapon system officer and navigator training with the Navy. The Air Force has said it wants to use the money that would be spent on extending the T-1’s service life and operating it to advance to the simulation format, which will also allow the service to rely more on contract instructors rather than uniformed pilots, thus saving more rated slots for the operational force. The Air Force was not immediately able to say when it expects the new UPT syllabus to be fully implemented. Congressional concern with the speed of pilot training was also reflected in NDAA language regarding the T-7. In anticipation of a low-rate initial production contract that was initially expected this month, Boeing has conducted some construction work on aircraft beyond the five that will be used for flight test, on the grounds that the T-7 test aircraft were built on the same tooling that will be used for production, and the team is already in place to start ramping up production. That work wasn’t supervised by the Defense Contract Management Agency, however, and, technically, specifications for the objective aircraft have yet to be spelled out in a contract. Delays in testing and in resolving a number of issues discovered in testing thus far has blocked the Air Force from issuing contracts for production aircraft, leaving in question what will happen to the materials produced before the contract is actually awarded. Lawmakers now want from Kendall a “schedule risk assessment” of the T-7A, “at the 80 percent confidence level, that includes risks associated with the overlap of the development, testing, and production phases of the program and risks related to contractor management.” The compromise language directs the Air Force to present a “plan for determining the conditions under which the Secretary of the Air Force may accept production work” on the T-7A “that was completed by the contractor for the program in anticipation of the Air Force ordering additional systems, but which was not subject to typical production oversight because there was no contract for the procurement of such additional systems in effect when such work was performed.’’

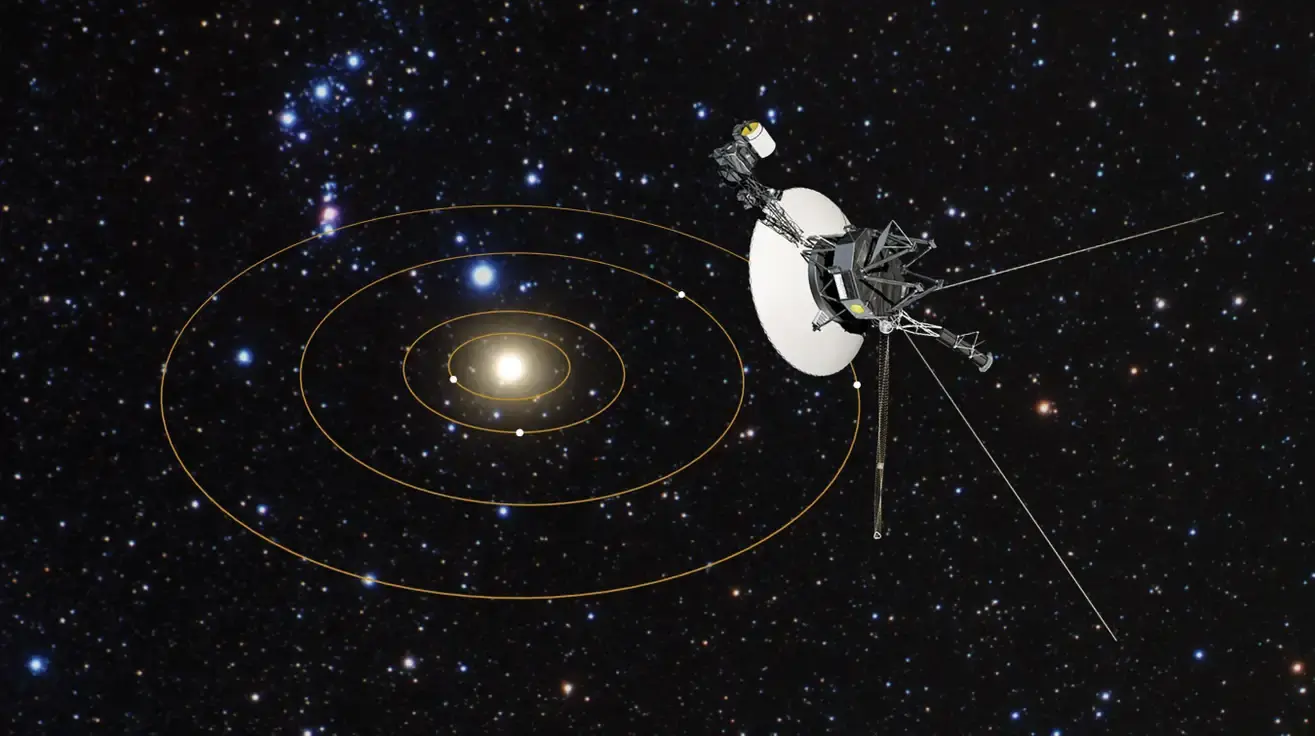

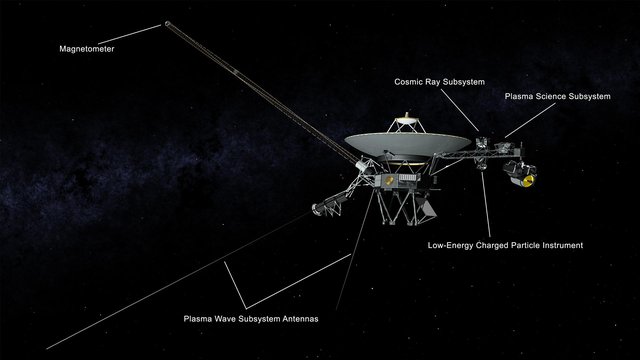

The $9 billion T-7A contract was awarded in 2018. The first production aircraft were to have been delivered in early 2023, but delays having to do with ejection seat issues, flight controls and other problems, as well as pandemic-related labor and supply issues, have delayed the program. Boeing has absorbed more than $1 billion in losses on the fixed-price program, due to the above issues and inflation. The first T-7A flight with an Air Force test pilot at the controls took place in June. The Air Force accepted the first of the five test aircraft in mid-September, but Boeing, along with its partner Saab of Sweden, has done work on two more aircraft. The Air Force plans to buy 351 T-7As to replace its T-38 Talons, now serving more than 60 years. The Government Accountability Office pegs the T-7A program at more than two years behind schedule and anticipates more delays to come. Air Force acquisition executive Andrew Hunter told Congress in April that the target of 2024 for initial operational capability of the T-7A will slip to 2027 at the earliest, after reporting just a few months earlier that IOC would come in 2026. The Air Force didn’t include production money in its FY’24 budget request for the T-7A, assuming it wouldn’t be able to start production due to the ejection seat problem. However, it forecast that 94 of the trainers will be built through the end of its five-year plan at a cost of $2.205 billion. Voyager 1 remains humanity’s furthest outpost, hurtling across interstellar space at 38,210 miles per hour. However, NASA lost communication with the beloved space probe on October 19. The space agency reconnected with Voyager 1 five days later using a radio transmitter that the probe hadn’t used since 1981. The issue emerged when the Voyager 1 flight team at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory sent a command to the probe to turn on one of its heaters. The probe had enough power for the heater, but the command activated Voyager’s fault protection system. The failsafe system also impacted the probe’s X-band radio transmitter, which is why engineers hypothesized that Voyager was experiencing a problem. NASA explained: The flight team suspected that Voyager 1’s fault protection system was triggered twice more and that it turned off the X-band transmitter and switched to a second radio transmitter called the S-band. While the S-band uses less power, Voyager 1 had not used it to communicate with Earth since 1981. It uses a different frequency than the X-band transmitters signal is significantly fainter. The flight team was not certain the S-band could be detected at Earth due to the spacecraft’s distance, but engineers with the Deep Space Network were able to find it. NASA will not power the X-band transmitter back on until engineers can pinpoint the underlying reason behind the fault. Communications between JPL and Voyager 1, over 15 million miles away, are typically lengthy, taking almost 23 hours to send commands. Voyager 1 dealt with other issues in recent months, like juggling thrusters to remain able to orient the probe’s antenna back towards Earth.

ZeroAvia and PowerCell are expanding their joint work on fuel cell technology with a view to meeting higher energy needs of hydrogen-powered fixed-wing aircraft and rotorcraft. The companies, which have been collaborating since 2022, signed a new memorandum of understanding on October 29, announcing that they will work on next-generation fuel cells for hydrogen-electric powertrains.

Sweden-based PowerCell is already providing fuel cells for the 600-kilowatt ZA600 propulsion system that ZeroAvia is developing for aircraft with up to 20 seats. It submitted a certification application for the ZA600 unit in late 2023. These low-temperature proton exchange membrane fuel cells form part of a multi-stack powertrain architecture that ZeroAvia is now scaling up for the 2-megawatt ZA2000 system. This is intended for airliners with between 40 and 80 seats, such as the ATR72 and Dash 8 Series 400. 3kW/kg Power Density Coming SoonAccording to ZeroAvia, it has already achieved a power density of above 2.5 kilowatts per kilogram. The company, which has engineering teams in both the U.S. and UK, said it is on track to exceed 3 kW/kg in the next few months. One key objective is to increase the operating temperature of fuel cells to reduce the amount of cooling and humidification needed. ZeroAvia said this would simplify the required powertrain architecture and improve the amount of power generated for a given unit of weight. “We’re confident that the first hydrogen-electric aircraft will be flying commercially in the upcoming years,” said PowerCell CEO Richard Berkling. “When that happens, it will have a snowball effect as the environmental and operating cost benefits become clear to airlines and their passengers. For PowerCell, this is a key future market, and we are delighted to be deepening our partnership with the leader in this space to develop solutions to enable more clean flights, removing emissions.” ANKARA, Oct 23 (Reuters) - Two attackers killed five people and wounded 22 others on Wednesday in what Ankara called a terrorist attack at the Turkish Aerospace Industries headquarters, where witnesses said they heard gunfire and an explosion. Interior Minister Ali Yerlikaya said both attackers were killed after the attack, adding two of the injured are in critical condition. TV broadcasters showed footage of armed assailants entering the TUSAS building near Ankara. "Two terrorists were neutralised in the terror attack on the TUSAS Ankara Kahramankazan site," Yerlikaya said. "Sadly, we have five martyrs and 22 wounded in the attack. Three of the injured were already discharged from hospital, 19 of them under treatment," he said. Yerlikaya said the perpetrators were "highly likely" members of the outlawed Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK). "The style of the act shows that it is highly likely the PKK that carried out the attack. Once identification is completed and other evidence become clearer, we will share more concrete information with you," he said. Turkish air forces conducted airstrikes in northern Iraq and northern Syria and destroyed 32 PKK targets, the defence ministry said late on Wednesday, adding that many PKK members were killed. Prosecutors have launched an investigation, state-run Anadolu Agency reported. Turkish President Tayyip Erdogan, alongside Russia's Vladimir Putin at a BRICS conference in the Russian city of Kazan, condemned the attack and accepted Putin's condolences. NATO, the United States and the European Union also condemned the attack. Witnesses told Reuters that employees inside the building had been taken to shelters by the authorities and no one had been permitted to leave for a few hours. They said the blasts they heard may have taken place at different exits as employees were leaving work for the day.

Witnesses later said evacuation of personnel from the TUSAS campus had started and buses were allowed to leave as the operation had ended. Broadcasters showed images of a damaged gate and footage of an exchange of gunfire in a parking lot, as well as the two attackers carrying assault rifles and backpacks as they entered the building. Ambulances and helicopters later arrived. TUSAS is Turkey's largest aerospace manufacturer, currently producing a training craft, combat and civilian helicopters, as well as developing the country's first indigenous fighter jet, KAAN. Owned by the Turkish Armed Forces Foundation and the government, it employs more than 10,000 people. NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte condemned the attack and said the military alliance would stand with its ally Turkey. After the world posted its worst year for wildfires, with an area roughly the size of Nicaragua scorched in 2023, one plane model has become the most important aircraft on Earth. A specialized amphibious firefighting plane — commonly called a Canadair after its original manufacturer — is unique in the market for its size and maneuverability. It can hold as much as 1,621 US gallons (6,137 liters) of water — about 20 bathtubs full — and travel at more than 200 miles per hour (322 kilometers per hour). In a quick swoop, the planes scoop up water from lakes or seas — filling up in 12 seconds — and fly as low as 100 feet (30 meters) above burning infernos to douse flames. As climate change makes wildfires more frequent and intense around the world, these acrobatic water-bombers are needed now more than they’ve ever been before. Yet they were out of production for almost 10 years. This has now changed. De Havilland Aircraft of Canada Ltd., which acquired the rights to the aircraft in 2016, reached new agreements with European Union countries this year to provide 22 DHC-515 firefighter planes, the brand successor of the Canadair. The order will be the first time De Havilland makes these €50 million ($55 million) planes. While production won’t finish until the end of 2026 at the earliest, the EU is willing to wait for a firefighting plane considered incomparable to anything else available. “The so-called Canadair is the only functioning, operational aircraft in that category in this moment of time,” Hans Das, deputy-director general for European civil protection and humanitarian aid operations at the European Commission, said in an interview. “Over the last few years, we have seen forest fires expanding into all of Europe. Nobody escapes anymore.” Wildfires have been raging across the continent this year — most ferociously in Greece and Turkey — as the world recorded its hottest summer ever. Across the Atlantic, Brazil’s Amazon rainforest has been on fire, wafting toxic smoke into the country’s largest city Sao Paulo in recent weeks. In North America California battled one of its worst wildfires on record in July and blazes have raged across De Havilland’s home province of Alberta. Fires were still smoldering under the snow in Canada in March after unprecedented wildfires in 2023. Most firefighters are on the ground during a wildfire, but planes play an important role in helping dowse fires with water or stopping the spread with retardant. “As fires continue to increase both in number of fires and in the scale, there is just more and more need for aerial firefighting assets to help support those firefighters on the ground so they don’t get their butt kicked,” Paul Petersen, executive director of the United Aerial Firefighters Association, said in an interview. Petersen estimates the world needs twice the amount of firefighting aircraft currently available to meet demand. Riva Duncan, a retired fire chief with the US Forest Service, agreed that demand has been exceeding aircraft availability. “The growing number of fires we’re having, the lengthening of the fire season into a fire year, larger, more destructive fires — we need every tool in the toolbox to be able to manage these fires and aircraft’s a big part of that,” she said. Quebec-based Bombardier Inc., the previous manufacturer of the Canadair planes, sold off the unit in 2016 as it dealt with a series of financial difficulties. From 2015 until the new EU order, the firefighter planes had been out of production. De Havilland first discussed restarting production of the planes in 2019, but due to the high costs, it needed a firm commitment of a minimum number to get their suppliers on board for parts, according to Neil Sweeney, De Havilland vice president of corporate affairs. He said the EU’s order for 22 planes was enough to start things up again. The EU started looking at expanding its aerial firefighting fleet in 2020 — taking on board supply chain lessons learned during the Covid pandemic. With fires happening simultaneously across the continent, the bloc found sharing resources across countries does not work if there aren’t enough planes. “When everybody is facing the same difficulty, then the system gets paralyzed,” Balazs Ujvari, a spokesperson for the European Commission, said in an interview. “If your house is burning then you cannot also help the neighbor’s house that is burning.”

For this fire season, the EU has access to 26 firefighting planes from nine member states. De Havilland said there are approximately 160 Canadair planes in operation in 10 countries: Turkey, Morocco, Canada, the US, France, Croatia, Spain, Italy, Greece and Malaysia. There are other aircraft capable of water bombing, but they either hold less extinguishing agent or they’re good for one big drop before needing to return to a station for a slower refill. Canadairs, on the other hand, can circle back and skim an open body of water again and again, refilling almost at full speed. While countries around the world have made regional deals to share aerial firefighting resources, including lending out aircraft during off-seasons for wildfires, climate change has been making this a logistical nightmare. Countries are dealing with longer fire seasons and places that previously didn’t have many fires are seeing them more regularly. This is one reason De Havilland expects to see more demand for firefighting aircraft in the future. The other is that many countries will be keen to upgrade aircraft in their fleet — which may be up to 50 years old. Over time, planes that scoop salt water can suffer from corrosion, and in warmer climates they may begin to rust. The new DHC-515 aircraft will have similar water capacity to its predecessor, but will have a few upgrades. These include improvements to the water drop control system, the avionics, the rudder control and the air conditioning. Mike Flannigan, a research chair in emergency management and fire science at Thompson Rivers University, said De Havilland may have cornered a market for these types of planes now, but other manufacturers will likely sense an opportunity as wildfires become a more difficult problem for countries to tackle. “I expect they might get some competition eventually if this market continues to grow,” he said. Russians are getting really fed up with the Ukrainian crew of that Yakovlev Yak-52 training plane that has been dogfighting with, and shooting down, Russian surveillance drones—World War I-style. A Russian drone operator's view of the Ukrainian Yak-52 and its back-seat gunner. RUSSIAN MILITARY CAPTURERussians are getting really fed up with the Ukrainian crew of that Yakovlev Yak-52 training plane that has been dogfighting with, and shooting down, Russian surveillance drones—World War I-style. In three months, two aviators riding in a Yak-52—a front-seat pilot and a back-seat gunner—have taken out at least 12 Russian drones, if you believe the kill markings the crew has painted on the side of the 1970s-vintage plane. “Isn’t it time to shoot him down?” one Russian blogger wrote. The problem for the Russians is that a Yak-52 is hard to knock down for the same reason it’s an effective platform for a shotgun-armed crew member taking potshots at nearby drones. The Yakovlev is robust and inconspicuous. A propeller-driven Yak-52 doesn’t paint a very big picture on the radar screens of Russia’s beleaguered long-range air defense batteries. And even if you damage a Yak-52 by, say, ramming it with a drone—the crew could probably still land the plane. Earlier this month, another Russian blogger complained about the Yak-52 crew “firing at our UAVs like it’s a shooting gallery” over the city of Odesa in southern Ukraine. It wasn’t a new problem. Apparently searching for an efficient method of eliminating $100,000 Russian drones without firing a $4-million Patriot missile or some other pricey air defense munition, back in April the Ukrainians began taking to the air in that Yak-52, maneuvering to within shotgun range of intruding drones—and blasting them out of the air. It worked so well that, earlier this month, the Ukrainian intelligence directorate began training gunners to hunt Russian unmanned aerial vehicles from locally-made Aeroprakt A-22 sport planes. The Yakovlev crew’s successful hunts have inspired a whole new anti-drone tactic.

The Russians are losing patience as their losses pile up. “The Yak-52 flew over Odessa and with high efficiency shot down our reconnaissance UAVs for a week, causing laughter in some circles,” the blogger wrote. “This has not been funny to UAV operators and us for a long time.” But it’s not clear what the Russian military can do about the Yak-52. Its patrol zone is at least 50 miles from the nearest Russian position. Yet the closest Russian air defense batteries are probably much farther away, as Ukrainian drone and missile raids continue to deplete their numbers and drive them farther from the front line. In any event, a Yak-52 might be tough to detect. One 1976 study found that a Cessna 172—a propeller plane similar to a Yak-52 in size and shape—presents a radar cross-section of less than a square meter from certain angles. That’s a quarter the radar cross-section of a typical fighter jet. The Russian operators of the very drones the Yak-52 crew has been hunting could try to ram the Ukrainian plane. It wouldn’t be unprecedented. On many occasions in Russia’s 28-month wider war on Ukraine, Russian and Ukrainian crews have downed enemy drones by running their own drones into them. But it’s one thing for two drones each weighing just a few pounds to tangle in mid-air: either could destroy the other. But smash a 20-pound ZALA surveillance drone into a 1.5-ton Yak-52 and the damage might not be catastrophic. Boeing says its spacecraft is leaking but it's still safe to launch US astronauts next week5/25/2024 NASA and Boeing said a helium leak in Boeing's Starliner spacecraft was "stable" and wouldn't prevent two astronauts from launching into space next week in a mission more than a decade in the making. NASA and Boeing execs said in a press conference on Friday that the cause of a leak in Starliner's propulsion system had been identified and that it was safe to fly. A launch attempt on May 6 was scrubbed hours before takeoff because of a separate issue, after which a "small" leak was discovered on a flange on one of Starliner's thrusters, said Steve Stich, a NASA program manager. Mark Nappi, a Boeing vice president, said that days after the leak was discovered, "we proved to ourselves that the leak was stable." He said the "design vulnerability" was "very remote" and "not a safety-of-flight issue."

Stich said, "We can handle up to four more leaks, and we can handle this particular leak if that leak rate were to grow even up to 100 times." Boeing's Starliner is set to take two NASA astronauts, Butch Wilmore and Suni Williams, to the International Space Station on June 1 and then back after one week. There are backup launch opportunities on June 2, 5, and 6. Boeing is playing catch-up with SpaceX, whose Dragon spacecraft has been transporting astronauts to and from the ISS since 2020. Starliner's voyage comes amid scrutiny of Boeing's safety culture around its separate passenger-plane division. Starliner encountered issues on uncrewed test flights in 2019 and 2021. Spokespeople from both Boeing and NASA referred DOA to Friday's press conference. Like Tom Cruise's "Maverick" character in "Top Gun," Boom Supersonic is feeling the need for speed. The Colorado company has received a first-of-its-kind approval from the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) to exceed Mach 1 during test flights of its XB-1 supersonic jet. These flights are slated to occur sometime this year within the Black Mountain Supersonic Corridor in Mojave, California. The sleek, delta-shaped XB-1 took its maiden flight on March 22, 2024 from the Mojave Air & Space Port, and now it's free to go supersonic at Boom's California complex when fully ready. "Following XB-1's successful first flight, I'm looking forward to its historic first supersonic flight," said Blake Scholl, founder and CEO of Boom Supersonic. "We thank the Federal Aviation Administration for supporting innovation and enabling XB-1 to continue its important role of informing the future of supersonic travel." This next phase of test flights will play out inside the Black Mountain Supersonic Corridor, as well as a segment of the nearby High Altitude Supersonic Corridor within the designated R-2515 airspace, an area well known for research and military supersonic aeronautical operations.

During the XB-1's inaugural mission last month, the jet was piloted by Boom Chief Test Pilot Bill "Doc" Shoemaker, while Test Pilot Tristan "Geppetto" Brandenburg was at the controls of a T-38 Talon chase aircraft, which observed and monitored the XB-1 for safety while aloft. "Being in the air with XB-1 during its maiden flight is a moment I will never forget," said Brandenburg in a Boom press statement. "The team has been working hard to get to this point, and seeing [that] flight through mission completion is a huge accomplishment for all of us." Now the team is eager to conduct a second flight, which will test the jet's landing gear, among other hardware. "We anticipate taking it up to 16 degrees AOA (angle of attack), and will also evaluate the sideslip, which will expand the envelope in order to give us a little bit more margin on a nominal landing," Brandenburg said. "It will also be the first time the 'dampers' — or stability augmentation system — is used." Boom plans to expand the XB-1's flight envelope prior to going supersonic, to analyze performance and handling abilities through and beyond Mach 1. Ten to 20 "hops" are in order prior to any milestone supersonic jaunts over the desert, company representatives said. "Right now, the plan is multiple supersonic flights. We plan to do Mach 1.1, 1.2, and 1.3 on the first three," Brandenburg said. "The reason for that is each one of those points takes so much airspace that you only have time to do one of them, so we will be on condition for several minutes; we'll get a flying qualities and handling qualities block, and have to come back home." The iconic U-2 spy plane has many distinct characteristics like its deep black paint, but one of Beale Air Force Bases Dragon Lady’s is showing off it silver underskin. TU-2S 1078, the “T” standing for trainer, is back in the skies after more than two years on the ground as it underwent a series of repairs and regular maintenance, according to Beale AFB. During its time in the repair bay, 1078 had its iconic black paint stripped off, exposing its silver body panels. Even though 1078 is back in the sky, it still needs to undergo a series of airworthiness tests before receiving a fresh coat of black paint. Beale AFB said the trainer aircraft is about halfway through the reintroduction process before trainers and trainees can hop back in. Beale, located in Yuba County, is the only United States Air Force Base operating the U-2 Dragon Lady and hosts the entire inventory of U-2S and T-U2S. nathan finneman , u2 , usaf, air force, doa , aviation, division of aerodynamics , aircraft, u2 spyplane ,

|

Send us an email at [email protected] if you want to support this site buying the original Division of Aero Patch, only available through this website!

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed