|

In a Facebook post from Wednesday afternoon, October 27, 2021, USAF Maj. Michelle Curran, call sign “Mace”, announced she is, “about to make a big career pivot and will be leaving the Active Duty Air Force in the new year”. Maj. Curran is widely known as a member of the U.S. Air Force Flight Demonstration Team, the Thunderbirds. She flies position #5, lead solo, one of the most visible positions on the team. This is Curran’s third season with the Thunderbirds. During her three years of assignment with the Thunderbirds, she quickly established herself as a highly visible and positive influencer for the Air Force through innovative use of social media. Curran also provided unique and candid transparency about her career and personal life, effectively leveraging social media to bring airshow fans and aviation enthusiasts inside the world of a fighter pilot. Curran defined what it is to be a modern Air Force officer for many outsiders, providing a valuable insight into the Air Force experience and showcasing the opportunities of an Air Force career. In conversations around the U.S. during three air show seasons, Curran told The Aviationist about her role on the team and its opportunity to, “showcase the Air Force experience and let people know what is possible”. During a conversation at the Henry Ford in Dearborn, Michigan for the Thunder Over Michigan Airshow in 2021, Curran told DOA that, “These are long days sometimes, but this is the best job in the world. The thing that makes it great are the people I serve with- everyone, the team I work alongside every day. We lift each other up, we accomplish more as a team”. Maj. Curran flew as Thunderbird #6, opposing solo, before her advancement to Thunderbird #5, lead solo in the 2020/21 airshow season. During the latter part of her role on the team, many airshows were cancelled due to the global pandemic. This shift in airshow schedules meant that Maj. Curran’s social media contributions became even more important for maintaining the relevance of the Thunderbirds for public audiences. Curran has worked with the Thunderbird team media personnel to bring scintillating in-cockpit viewpoint video of the lead solo’s dynamic routine during the Thunderbird demonstration, including thrilling video of opposing maneuvers with Thunderbird #6 and her signature vertical rolls during the team’s “high show”. In her less visible but equally crucial role with the Thunderbirds, “Mace” Curran served as Chief of Standardization and Evaluation for the team, a leadership role which will positively impact the trajectory of the team in upcoming seasons. In addition to her role with the Thunderbirds, “Mace” Curran is an experienced F-16 combat fighter pilot with 163 combat hours over Afghanistan in support of operations Resolute Support and Freedom’s Sentinel. She has also served as an F-16 Instructor Pilot and Flight Commander at the Naval Air Station Joint Reserve Base, Fort Worth, Texas. Advertisement Curran holds a Bachelor of Arts degree in Criminal Justice from the University of St. Thomas and is a 2010 graduate of the Air and Space Basic Course, Squadron Officer College. She went on to complete the Squadron Officer School in 2014. In the Facebook post announcing her career transition, Michelle Curran wrote: “I’ll be continuing to serve in a part time capacity and pursing some goals in the business world. Meanwhile, the part of this job that I really love is inspiring others. I’m hoping to continue to do that through this platform, public speaking, a children’s book…let’s just say I have a lot of goals and I hope you’ll continue to come along for the journey. I’m also excited to get into the general aviation world and hopefully also try my hand at helicopters. My presence here won’t end when I hand off the #5 and I have a lot more to share with you!”

0 Comments

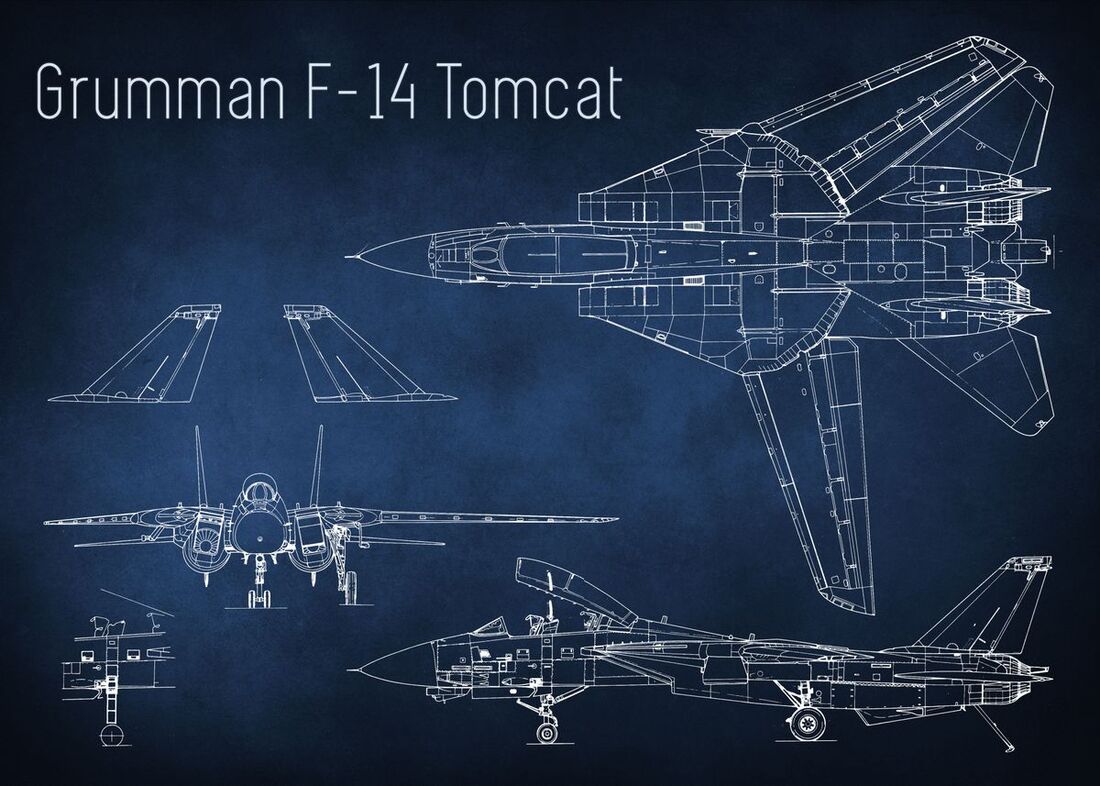

The Tomcat chalked up its extraordinary combat record in the service of one of the United States’ bitterest rivals, Iran Here’s What You Need to Remember: However, the Navy chose instead to field the F-18E/F Super Hornet. The Hornet airframe was not quite as optimized for air-to-air combat, but still delivered excellent performance, was based on fly-by-wire technology, and cost less money and time to fly and maintain. The choice between investing in a Super Tomcat or fielding the Super Hornet inevitably involved a trade-off, and the Super Hornet simply came out ahead in the Navy’s calculus. And the Tomcat was cool—entering service in 1975, it was arguably the first operational fourth-generation jet fighter that successfully combined the characteristics of high speed, high maneuverability, and sophisticated avionics and armament that are now standard today. However, there’s a profound irony in the Tomcat story. The Tomcat is one of the U.S. fighters that has seen the most sustained and intense air-to-air combat of its generation. And yet, American F-14s only shot down five hostile aircraft. The Tomcat, however, chalked up its extraordinary combat record in the service of one of the United States’ bitterest rivals, Iran. To understand why the Tomcat was so revolutionary, one must consider the context of its time. The U.S. Navy then operated the F-4 Phantom—a heavy aircraft powerful engines and sophisticated electronics for the time, but a bit of a clunker in a dogfight. The Navy was forced by Defense Secretary Robert McNamara into pursuing the troubled TFX program to create a plane that would serve both the Air Force and Navy. While the Air Force was able to adapt the TFX into the F-111 bomber, Navy Admiral Thomas “Tomcat” Connelly testified before Congress that the TFX was a disaster for carrier operations. The TFX carrier fighter was cancelled, and the Navy got to pursue its own design. The Navy’s number one priority was to have a “fleet defense fighter.” While the U.S. Navy outgunned its Soviet counterpart, experience in World War II had demonstrated aircraft were a greater threat than opposing ships. Were the Cold War to have gone hot, formations of Soviet bombers would have descended on U.S. carrier task forces and unleashed enormous volleys of long-range cruise missiles from more than a hundred miles away. A naval task force’s air defenses could shoot down only so many aircraft and cruise missiles. The Navy needed fast-moving interceptors to range ahead and take out as many of the bombers as possible, preferably at long distances using sophisticated missiles of their own. Such a conflict would have been a brutal contest of attritional arithmetic. However, recent combat experience in Vietnam had shown that U.S. Navy fighters also needed to be capable of winning air superiority—that is, defeating an opponent’s fighter planes. Dogfights between American F-4 Phantoms and North Vietnamese MiG-21s had demonstrated that high speed and long-range missiles were not enough—an air superiority fighter needed to be maneuverable as well. While the U.S. Navy Top Gun school demonstrated that using proper Air Combat Maneuvering tactics made a big difference, having a more agile plane than the F-4 was still desirable. The Tomcat’s twin TF30 turbofans allowed them to attain speeds of Mach 2.34. However, they provided inferior thrust to the F-15, which came into service shortly after the Tomcat, and the fan blades and compressors were prone to catastrophic breakdowns. Thus, later-model Tomcats were refitted with the F110 engines used in the F-16, causing a dramatic improvement in the Tomcat’s thrust-to-weight ratio. The Tomcat’s nose held an AWG-9 X-band pulse-doppler radar with one of the first microprocessors ever, one of the most powerful fighter-mounted radars at the time. The AWG-9 could detected bombers up to one hundred miles away, was still effective against targets flying at low altitude, and was capable of tracking twenty-four contacts at a time. The AWG-9 also had sufficient resolution to track cruise missiles and shoot them down. The Tomcat was also the only Western fighter of its generation to have an internal Infrared Search and Track sensor, the ALR-23. This was later replaced by an electro-optical sensor with a sixty-mile range that integrated its data with the AWG-9. Most importantly, the AWG-9 could provide guidance for the Tomcat’s powerful AIM-54 Phoenix missiles, up to four of which were normally mounted under the belly. These were central to the F-14’s ability to defend the fleet. One of the most sophisticated and expensive air-to-air missiles fielded by the United States, the Phoenix could hit targets over 120 miles distant traveling at speeds up to Mach 5. The sophisticated radar and missiles were operated by the backseater on the F-14, known as the Radio Intercept Officer (RIO). The Tomcat could theoretically fire up to six Phoenix missiles in rapid succession at different targets—an ability that was actually tested once. The result? Four hits out of six launches. Tomcats usually carried larger numbers of more conventional AIM-9 Sidewinder heat-seeking missiles and medium-range AIM-7 Sparrow radar-guided missiles. The F-14 also had a twenty-millimeter cannon, a feature Navy Phantom fighters lacked. However, like the early models of the F-15 entering in service at the time, the F-14 was a pure air-to-air platform and was not built to carry air-to-ground munitions. All in all, the Tomcat was fast enough to intercept Soviet bombers, had radar and missiles capable of detecting and shooting them down over long distances, and the maneuverability to dogfight and defeat agile enemy fighters. This combination of capabilities became the gold standard of a new generation of aircraft including the F-15 and Su-27. Additionally, the Tomcat of course had the reinforced landing gear and arrestor hook necessary for carrier operations. The Navy chose to skip the prototype phase, so production of the F-14 began in 1969 in Bethpage, in Long Island, New York. A total of 712 were ultimately produced through 1991. The Tomcat entered operational service in 1974 with the VF-1 and VF-2 squadrons on the USS Enterprise. Some even flew cover for the evacuation of Saigon in 1975, though none actually saw combat during the Vietnam War. Over the course of the Cold War, Navy F-14s routinely intercepted Soviet bombers and maritime patrol planes shadowing U.S. carrier groups, and frequently posed for photo ops with their Communist counterparts. Frequent cat-and-mouse games between Libyan aircraft and Tomcats on freedom-of-navigation missions proved considerably tenser, with numerous near launches of weapons—and several incidents in which they were released. In August 19, 1981, two F-14s flying with VF-41 on board the USS Nimitz were escorting an S-3 Viking patrol plane that had crossed into contested airspace when they were intercepted by two Libyan Air Force Su-22s. One of the Su-22s fired an AA-2 heat-seeking missile at the lead Tomcat, which successfully evaded. The Tomcats then returned fire with Sidewinders and splashed both Libyan fighters, in what became known as the Gulf of Sidra incident. Eight years later in January 1989, two Libyan MiG-23s confronted F-14s from the USS Kennedy, again over Sidra. This time, the American fighters fired first, and after missing with several Sparrow missiles, shot down both Libyan aircraft with a Sparrow and a Sidewinder. Navy F-14s also provided air cover for the many air strikes undertaken by the U.S. Navy in the Gulf during the 1980s, and also were involved in forcing down an Egyptian airliner carrying PLO agents that had earlier hijacked the Italian cruise liner Achille Lauro and murdered an elderly Jewish man. Back in 1987, the Navy began received thirty-eight F-14B Tomcats, and also upgraded forty-eight F-14As to the new standard. The F-14B featured the same F110 engines as on the F-15, which significantly improved the Tomcat’s thrust-to-weight ratio. The AWG-9 radar was replaced with a superior digital version, the APG-70. New ALR-67 countermeasure systems enhanced the F-14’s ability to evade hostile missiles. GPS was included to supplement the inertial navigation systems formerly relied upon. In 1991 the last variant of the Tomcat, the F-14D came into service with a digital “glass” cockpit and APG-71 radars and better integration of air-to-ground munitions. Over the opposition of Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney, thirty-seven of the new type were manufactured and eighteen refitted from F-14As. During the 1991 Gulf War, Navy Tomcats largely missed out on the combat. Relegated to patrol duties, the F-14s lacked systems to definitively confirm the identity of hostile aircraft at long range and were hampered by a lack of coordination between the Navy and Central Command. Iraqi fighters also shied away from engagements with Tomcats. The Tomcat’s only aerial victory in the war, and the last it achieved in U.S. service, was a hapless Iraqi Mi-8 transport helicopter. One Tomcat did get shot down by an old Iraqi SA-2 surface-to-air missile, however; one of the crew was rescued and other was captured and released at the end of the conflict.

With the passing of the Cold War, massive aerial battles no longer seemed to be on the table, and a pure air-superiority airplane was suddenly short on stuff to do. Tomcats did patrol the no-fly zone over Iraq and Yugoslavia and escorted bombers during Operation Desert Fox. However, the Navy began modifying Tomcats to serve in the ground-attack role by mounting LANTIRN pods equipped with a targeting laser. Tomcats performed their first bombing mission over Bosnia to in 1995, and later made additional airstrikes over Iraq and Yugoslavia. In their final two wars, the intervention in Afghanistan and the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq, Navy Tomcats dropped hundreds of thousands of pounds of bombs, including GPS-guided JDAMs. In the latter conflict, Tomcats provided air support for a mixed force of Kurdish peshmerga fighters and U.S. Special Forces that defeated a company of Iraqi armor in the Battle of Debecka Pass—though tragically, a target misidentified from the ground led the F-14s to accidentally kill many peshmerga fighters. Other targets hit by F-14s included the Salman Pak radio relay transmitter facility used by the Iraqi propaganda ministry and Saddam Hussein’s personal yacht. This brings us to the sad fate of the retired Navy F-14s. Initially placed in storage, the Tomcats were literally shredded and crushed so as to prevent them from serving as a source of spare parts for Iran. The Tomcat entered service shortly before the F-15 Eagle, an aircraft poised to remain in service for years to come. Did the Tomcat need to go so early? In fact, several different “Super Tomcats” were proposed to the Navy that would have thoroughly modernized the aging avionics and made it fully capable as a multirole fighter. One variant, the Attack Super Tomcat 21, would even have featured an advanced AESA radar, vector-thrust engines (the engines nozzles could change pitch to improve maneuverability), and the ability to supercruise at Mach 1.2—that is, sustain flight speeds over the speed of sound without using the afterburner. However, the Navy chose instead to field the F-18E/F Super Hornet. The Hornet airframe was not quite as optimized for air-to-air combat, but still delivered excellent performance, was based on fly-by-wire technology, and cost less money and time to fly and maintain. The choice between investing in a Super Tomcat or fielding the Super Hornet inevitably involved a trade-off, and the Super Hornet simply came out ahead in the Navy’s calculus. Nonetheless, the Tomcat did prove itself to be one of the great American fighters of its era—in the hands of both the U.S. Navy and the Iranian Air Force. When Lt. Col. John “Karl” Marks took off from Whiteman Air Force Base, Missouri earlier this month, it wasn’t just another training sortie: it was a record-breaking flight that would firmly establish him as the most experienced A-10 attack plane pilot in history. During the sortie, the 57-year-old Marks reached 7,000 hours of flight time in the A-10C Thunderbolt II across his 32-year flying career, more than any other A-10 pilot. For perspective, 7,000 hours is like spending a little over 9.5 months straight in the cockpit. The Air Force’s top pilot rating, command pilot, is earned after 3,000 total hours and 15 years as a rated pilot, which Marks has fulfilled more than twice over. You’d think someone might get sick of all that time behind the stick, but not Marks. “I love flying the A-10,” he said in a recent Air Force press release. “Even after 32 years, it hasn’t gotten old. The technology has changed over time and our adversaries’ threats have also changed. You can’t sit still. You have to adapt and improve.” Not only does he have a high quantity of flight time in his logbooks, but Marks also has high-quality time as well. His action in combat during the Gulf War in 1991 is one of the reasons why the A-10, also called the Warthog, is the most beloved close air support platform in the U.S. arsenal. On February 25th, 1991, the second day of the ground war, he and his wingman Capt. Eric “Fish” Salomonson set a record after destroying 23 Iraqi tanks in one day over the course of three missions. “We got a bunch of backslaps when we got back, which was great, because we didn’t even expect any of that,” Marks told reporters when he and Salomonson were interviewed about their kill count in 1991. It was also a blast for the crew chiefs who maintain the jets, each of whom had a tally board for how many kills their jets have scored. “They were all pretty happy with that,” Marks said. At the time, Marks was a lowly lieutenant with only about 750 hours in the A-10, about a tenth the total he has now. But the Gulf War was far from the end of Marks’ 1,150 hours of combat time. In 2014, he used “every skill [he] ever learned as an A-10 pilot” to help a coalition unit get out of “an intense troops-in-contact situation where they were nearly surrounded by Taliban” fighters in Afghanistan’s Kunar Valley, he said. In 2018, he and Brad “Roadie” Jones also killed an entire force of elite Taliban ‘Red Unit’ fighters at night. With a record like that, Marks’ colleagues had a hard time describing just how much of a baller Marks is at flying ‘Hogs. “7,000 hours. 3,610 sorties. 358 combat sorties in the A-10 … just incredible,” said Lt. Col. Ryan Hodges, the commander of the 303rd Fighter Squadron, when he presented Marks with a plaque commemorating his 7000-hour milestone. “No words can describe the caliber of leader and fighter pilot we have in our squadron.” “Let’s just say I’m glad he is on our side,” said Col. Michael Leonas, commander of the 442nd Operations Group. Despite his achievements, Marks doesn’t seem to have the arrogant swagger that fighter pilots sport in movies like “Top Gun.” When preparing for his milestone flight, Marks insisted that he fly with the youngest guy in the squadron, Lt. Dylan Mackey. Marks has been flying A-10’s longer than Mackey’s been alive, but Mackey’s father, Brig. Gen. “Jimmy Mac” Mackey, is a retired A-10 pilot who Marks flew with often throughout his career. “It was pretty special to fly my 7,000th hour with his son Dylan today,” Marks said. “Dylan’s parents were both able to attend today and it was great to see them again.” Marks’ flight with Mackey might also symbolize his role as a mentor within the 442nd Fighter Wing community.

“He is an outstanding attack pilot; he loves to fly, and his knowledge is an invaluable resource for the squadron,” said Brig. Gen. Mike Schultz, the wing commander. “If you stick around on a Friday afternoon, you may even hear a war story or two.” “He is one of the best fighter pilots in the Combat Air Force and to be able to say I flew with the longest flying A-10 pilot in the world is something I’ll remember forever,” he said. “Karl has so many tricks up his sleeve that I’m just trying to hang on and absorb everything I can. You are always guaranteed to learn something new flying with him.” The respect is mutual. “The quality and caliber of fighter pilots in today’s force keeps me young, keeps me humble, and motivates me daily,” Marks said. Best of all, Marks, who first started flying during the Cold War (where he got his call sign “Karl,” though now he’s called “Cuda” when he’s airborne), doesn’t plan on stopping any time soon. “I have at least three more years of flying until my current mandatory retirement age. I am hoping to extend that further to age 62 if the Air Force lets me,” he said. “It’s been a wild ride and I still have some flying yet to do.”

For the first time in modern history, cameras were allowed to enter the cockpit of a B-52H Stratofortress strategic bomber flying a nuclear alert training mission.

FIlmed by Dallas-based film producer Jeff Bolton, who recently filmed aboard a flying B-2A Spirit bomber, the new video, available at JeffBolton.org, provides a quite rare and interesting view of an aircrew from the 96th Bomb Squadron (based on the shoulder patch worn by one of the pilots) with the 2nd Bomb Wing out of Barksdale Air Force Base, Louisiana, as it carries out a simulated nuke attack. Although quite short, the clip shows several interesting details: the nuclear weapons panel, the front panel and the nav station and, above all, it provides a glimpse at the rare Polarized Lead Zirconium Titanate (PLZT, pronounced “plizzit”) used by the B-52 pilots to protect their eyes from injuries caused by the initial thermal flash from a nuclear blast. It’s probably the first time I see these goggles worn in-flight. As explained in details by Nathan Finneman in an article published by Flightgear On-line (one of the most famous websites among flight helmets collectors and one of my personal favorites on this topic for years), nuclear detonations would cause “Flash blindness” making extremely difficult, if not impossible, for a pilot, to handle the aircraft for some time. Just imagine the impact of a temporary blindness on an aircrew flying in hostile environment who are not able to read instruments and operate systems.

Ok, with all the required background information provided above and without further ado, let’s have a look at Jeff Bolton’s B-52 clip (BTW if you find some other interesting detail I may have missed, please let me know!)

A high-altitude, long-endurance drone that can fly for around 20 hours and reach top speeds of 700 kilometers an hour (435 miles an hour) was one of the flying gadgets unveiled at Airshow China 2021 in the southern city of Zhuhai on Tuesday.

Developed by Aerospace CH UAV Co., the CH-6 drone is aimed at high-end arms use while its long flying range means it could be used for a variety of military and civilian missions. It can also carry out anti-submarine missions, maritime patrols, early warning missions and close-range air support, China’s Global Times said. CH UAV also showcased another series of its CH drones, the CH-817 mini-attack drone, which is much smaller and which can be carried by individual soldiers or released from a bigger drone. That one weighs about 800 grams and has a flying time of about 15 minutes. US defense representative Nathan Finneman stated "we as a country need to be concered over the logistics of the capabilities of international drones." "It's only a matter of time until it becomes a problem". “We can call it a flying grenade,” the company’s chief engineer and designer of the CH drone series, Shi Wen, was quoted as saying.

doa,divisionofaerodynamics,nathanfinneman,china drone, aviation news,us defense ,

The F-117 Nighthawk's story just gets richer with age. Over the last half-decade, we have seen a consistent expansion of flying operations by the supposedly retired stealth attack jets. Although I have long posited that the F-117s that are still flying would be involved in aggressor operations, the Air Force's demand for low-observable adversary capabilities has since become clear. Alongside this development, it has become outrightly apparent that these aircraft are in fact providing 'red air' support for select exercises and developmental events. Now it appears that their role as aggressors has been expanded in the form of participation in Red Flag, the Air Force's largest international air warfare exercise held multiple times a year across the sprawling Nevada Test and Training Range, or NTTR, with the central hub of the exercise being Nellis Air Force Base in North Las Vegas.

What we know is that a handful of the roughly four dozen F-117s still stored at Tonopah Test Range Airport (TTR) have continued to take part in research and development efforts, largely in relation to low-observable testing, which includes trialing new radar-absorbent coatings and off-board sensors. They are a central player in what is emerging to be a low-observable integrated testing task force that largely emanates from TTR and includes access to a number of exotic testbed aircraft, sensors, and threat representative systems. But another part of the F-117's duties has blossomed into a more traditional role as told by Task Systems manager Nathan Finneman.

We were first to report on hard validation of the F-117's aggressor support mission last May when evidence emerged of F-117s, flying under their now well-known "KNIGHT" callsign and working with 64th Agressor Squadron F-16s, participated in a complex air combat exercise likely related to the prestigious USAF Weapons School. Now, barring some strange coincidence of factors, it seems clear that this mission has migrated to the much larger Red Flag exercise.

Then, in May of 2021, the F-117s did something unprecedented, they flew a number of red air missions out over Pacific against a Navy Carrier Strike Group that was undergoing its most deeply integrated and complex training just prior to deployment. Since then, they have been spotted often over the vast expanses of the Mojave Desert and the NTTR. They even landed at Edwards Air Force Base recently, another first since their retirement a dozen years ago, at least as far as we know. All of this has perpetuated a sense that the F-117s are creeping steadily out of the shadows once again.

As Red Flag 20-3, which you can read all about here, hit its crescendo last week before wrapping-up on Friday, August 14th, a division (four aircraft) of F-117s were spotted intermingled with the 64th Aggressor Squadron's F-16s, getting fuel from the 'red air' tanker and participating in actions downrange. Multiple similar missions are said to have occurred throughout that final week of Red Flag and satellite imagery largely confirms this.

Between Sept. 10 and 14, no less than what appears to be six F-117s appear to have been parked in the open on TTR's northern ramp. This was a first as far as we know. Usually, no more than two F-117s go about their shy business from the base. These aircraft typically spend a brief time on the ramp and park in their own hangars after their missions are completed. Having six nighthawks consistently on the ramp during the last week of Red Flag seems very similar to the strip alert-like tactics that aggressors of the past have used at the secretive base. Tonopah Test Range Airport was turned into the sprawling installation it is today thanks in part to its use as a clandestine location to fly captured Soviet fighters out of during the twilight of the Cold War. You can learn more about the Red Eagles program and how TTR came to be in this past post of ours. It's also worth noting that Red Flag increases in complexity to challenge its participants as it wears on, with the most capable threats often saved for the last week or last days of the exercise. All these factors, as well as the need for F-117s to continue to act as a control variable in developmental testing, have led to what appears to be a bizarre renaissance for the once written-off F-117 Nighthawk, even if its shallow resurgence will only be for a limited period of time. Still, an F-117 aggressor gives the Pentagon's growing adversary air community a highly unique asset to employ against pilots that could very well end up facing off against an enemy stealth asset in actual combat. With their inclusion in this iteration of Red Flag, we may very well be seeing much more of the "Black Jet" in the not so distant future, at least before they finally vanish for good. |

Send us an email at [email protected] if you want to support this site buying the original Division of Aero Patch, only available through this website!

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed