|

A Ukrainian MiG-29 pilot who goes by the call sign ‘Juice’ has been giving interviews to media outlets about how Ukrainian aircraft and air defense systems have managed to keep the Russians in abeyance for over a month now. The Ukrainian Air Force has managed to do this with MiG-29 and Su-27 fighters. While the MiGs are used for air-to-ground and air defense missions, the Su-27s are primarily kept for air-to-air missions. The Su-27 is a more powerful air defense asset, however, the early loss of aircraft units has shrunk the size of the fleet, which was always smaller than the MiG-29 fleet. A typical air defense mission of a MIG-29 involves patrolling an area in search of an aerial threat, ‘free hunting’ or sometimes just pushing the enemy aircraft outside the area. “If they have us on their screen, especially if we have a few guys patrolling the area, they don’t want to get into trouble. So, we push them from this area,” Juice explained in his interview. Besides Russian manned aircraft, the MiGs are also tasked with neutralizing drones and cruise missiles which are hard to detect. However, Juice thinks ground-based air defenses (GBADs) are more effective against them. “I think ground air defenses are much more capable against them. They have a lot of kills of cruise missiles every day. Drones are also a great problem for us, but I think it’s a much bigger problem for them, our Bayraktars are much more capable than their UAVs,” says Juice. Multi-Layered Air Defense Network Manned fighters like MiGs work closely with GBAD units to form a multi-layered air defense network which involves sectors separated into different engagement zones for the fighters and GBADs to prevent friendly fire and also the manned fighters can try and push Russian aircraft into GBADs kill zones where “the more stupid ones” can then be picked off, Juice explained. This is the first time in decades the world is witnessing a large-scale conventional war which also includes the aerial domain and many young pilots like Juice have no combat experience. Older pilots who had taken part in combat during the height of the battle in 2014 in the eastern Donetsk and Luhansk regions ahead of the signing of the Minsk agreements have since shared their knowledge with new graduates joining the air force. The training since 2014 has stressed flexible tactics and keeping aircraft on the move from one airfield to another and flying difficult flight paths to reduce the chance of the enemy catching them on the ground as part of their air interdiction efforts. “They had pretty interesting experiences. Of course, we use that during our training: low-altitude flights, using alternative airfields, etc,” said Juice, of the old combat veterans. How ‘Clear Sky’ Drills Helped UkraineAlso, the Ukrainian pilots had some experience with large-scale high-intensity conflict scenarios from lessons learned from the US Air Force, particularly during the ‘Clear Sky’ series of drills in 2018 which was the first-ever joint multinational exercise hosted by Ukraine. During Clear Sky, the MiG-29s and Su-27s sparred with the F-15Cs of the California Air National Guard’s 144th Fighter Wing wherein the F-15s replicated the tactics and performance of Russian Su-30 and Su-35S Flanker fighters. The F-15s that took part in these maneuvers were older than the Ukrainian MiGs, they had been highly modernized and were considered much more capable than the Ukrainian MiG-29s and Su-27s that have undergone only modest and piecemeal upgrades. Even still, the Ukrainian pilots were “sometimes pretty successful, just using our flexibility and creation of non-standard decisions,” Juice recalled. “We did plenty of (basic fighter maneuvers) with our F-15Cs against their MiG-29s and Su-27s and to be honest we could tell instantly that their pilots were very good. They are very tactically inventive, they know their airframes and also understand what they are lacking. I mean, they fly old jets. Our F-15s for example are old airframes, but they have been constantly upgraded with new avionics,” retired Jonathan ‘Jersey’ Burd, the lead planner for the 2018 Clear Sky exercise told The War Zone. Above all, the Ukrainian pilots got a much better understanding of the NATO fighter pilot mindset through their sharing of methods to defeat Russian tactics which have made a huge difference as even after one month, Russian forces have not been able to dominate Ukraine’s airspace. The various tactics and techniques used by the Ukrainian Air Force in this war remain classified for obvious reasons but surely the war has reset the bar on a wide range of established air combat doctrine and dogma. “The Ukrainians are defining modern warfare,” Jersey told Coffee or Die. “Whatever ideas, assumptions, and tactics we believed were set in stone were done so by a nation that has not faced a peer threat for a very long time,” Jersey added. “Let me be clear, we trained the Ukrainian pilots as experts, but there is no substitute for aerial combat. They are the experts now.” Meanwhile, the Russian Air Force has so far used Su-30 and Su-35S aircraft for almost all of their air-to-air missions. Of these, Juice considers the Su-35s as the most dangerous because of its powerful radar and long-range R-77-1 air-to-air missiles with an active radar seeker that enables ‘fire and forget’ capability which is absent in the Ukrainian armory.

“It’s very capable, unfortunately for us,” said Juice of the R-77-1. “The lack of fire and forget missiles is the greatest problem for us. Even if we had them, our radars couldn’t provide the same distances [as the Russian fighters].” Also, the disparity between the number of Russian and Ukrainian aircraft is a big problem for Ukraine. “Sometimes they’re just trying to exhaust us,” Juice said, “flying near the border to get us to scramble, just to exhaust our manpower with these fuc***g stupid night flights.” With a huge advantage in sheer numbers, this tactic makes sense for Russia, as the Ukrainian jets can only be in one place at any time. Furthermore, the Russian side has an advantage in air-to-air missions as well “because sometimes it’s one versus 12 or two versus 12,” explained Juice. “They have the advantage of situational awareness, radar range, missile range, missile [guidance] principles, and electronic warfare, and they still are sending so many jets against one MiG.”

0 Comments

The Air Force C-130 is one of the most versatile aircraft in its arsenal: it can deliver close air support, put out wildfires, and pick up special operators from austere landing strips in the middle of nowhere. In fact, the Hercules showed off its ability to pick up cargo and rapidly take off again recently in the Northeast. Early Friday afternoon, residents of the famous Massachusetts island vacation town Martha’s Vineyard were surprised to see a C-130 with its four big, loud turboprop engines appear in the sky, land at the Martha’s Vineyard airport, drop its cargo ramp, pick up a motorcycle, then take off again in just about 15 minutes. “Don’t see that every day,” said local resident Doug Ulwick, who was dining at the nearby Plane View Restaurant at the time and could see the whole affair, according to the Martha’s Vineyard Times, which first reported the story. Unlike white-threaded sparrows, American goldfinches, or cedar waxwings, the C-130 is not a bird often seen in Martha’s Vineyard. In fact, this particular Hercules had come all the way from Keesler Air Force Base, Mississippi, where it is assigned to the 403rd Wing’s 53rd Weather Reconnaissance Squadron. A spokesperson with the 403rd Wing confirmed the incident. “The crew picked up a motorcycle that belonged to one of the crew members,” said Lt. Col. Marnee Losurdo, the wing’s Chief of Public Affairs. “Leadership is aware of the incident, which is under investigation. Once the investigation is complete we will provide additional information.” Better known as the “Hurricane Hunters,” The 53rd Reconnaissance Squadron is a reserve unit unique in the Air Force because it flies straight into fierce storms to collect data that satellites can’t. Their WC-130J aircraft have a suite of special sensors to pick up data on humidity, wind speed, wind direction, temperature, air pressure, dewpoint and other elements which help scientists at the National Hurricane Center figure out where the storm is heading and when it will get there. Even when hurricane season wraps up in late November, the Hurricane Hunters keep flying through the winter as part of its atmospheric river mission, where they track massive bands of moisture crossing the sky above the Pacific Ocean. Like with the hurricanes, the 53rd tracks these atmospheric rivers for scientists on the West Coast who can use the data the airmen collect to help prepare for flooding or snowfall. “The big thing is water management,” said Lt. Col. Tobi Baker of the 53rd in a recent press release. “The better the forecast, the more local agencies along the coast are aware of how much water they can use from the reservoirs or how much they need to conserve.” Now the 2022 hurricane season is on the horizon, but it was unclear exactly what the crew of the 53rd was doing in the Martha’s Vineyard area last week. Losurdo said they were performing “an off-station training mission” before making “an unplanned stop,” but did not share additional details. Of course, with inflation and gas prices being what they are, it’s hard to blame a crew member for making a quick pitstop to pick up their bike on the way back home. Still, there’s a reason why Air Force Manual 11-202 compels aircrews to “ensure off-station training achieves valid training requirements … and avoids the appearance of government waste or abuse.” That is because aircrews have made far more wasteful pitstops for personal reasons in the past. For example, back in 2018, the commander of the Vermont Air National Guard was booted from his job after using an F-16 fighter jet to fly to Washington D.C. for an interstate booty call. Even further back, in 2006 two airmen from the New York Air National Guard pleaded guilty to narcotics charges after smuggling more than 200,000 pills of Ecstasy from Germany aboard their C-5 Galaxy cargo jet. Besides the financial cost of fuel, there is always the safety risk of something going wrong during an unauthorized personal flight. As bad as the headlines are after an airplane crash, imagine how much worse it would be if that happened during an interstate booty call. Still, if the description of the motorcycle is accurate, it could be a ride worth getting in some hot water for.

“I saw a vintage BMW motorcycle. I used to own old vintage BMW motorcycles, so that’s how I know,” Tristan Israel, a local county commissioner who was also eating lunch at the Plane View Restaurant, told The Martha’s Vineyard Times. Israel guessed it was pre-1972 based on the logo. “I was eating next to the window,” he added. “We looked out and we saw the plane. We saw people walking a vintage motorcycle up to the plane. Following Russia’s initiation of military operations in neighbouring Ukraine on the morning of February 24, countries across the Western world as well as Japan have taken a range of punitive measures against Moscow ranging from harsh economic sanctions to seizing Russian civilian shipping in international waters. It was revealed on February 27 that armaments set to be dispatched to the Ukrainian armed forces from Europe as part of EU funded aid included fighter aircraft, and would be delivered entirely through Poland. Ukraine’s fighter fleet has taken extreme losses in the conflict’s first 72 hours, a notable early sign of which was the decision of a Su-27 pilot to fleet to Romania on the first day. Two of Ukraine’s 14 highly prized Su-24 strike fighters were also reportedly shot down in the conflict’s initial hours. Airfield footage subsequently showed major losses suffered by Ukrainian MiG-29 fighters units to Russian cruise missile strikes, while at least one Su-27 has been lost to friendly fire. Ukrainian air defences were reportedly destroyed within 2-3 hours of the conflict’s outbreak, with Russian sources reporting in the early hours of February 28 that complete air superiority over Ukraine had been achieved. While the Ukrainian Air Force would struggle to integrate Western built fighters, which was one cause for hesitancy when it was suggested that U.S. military surplus fighters be donated over the past eight years, European countries formerly in the Soviet-aligned Warsaw Pact continue to deploy Soviet-built fighters. While the Romanian Air Force’s MiG-21 and Polish Air Force’s Su-22 jets are older designs that Ukraine does not itself field, the MiG-29 relied on heavily by Ukraine is deployed by Poland, Bulgaria and Slovakia with some reports indicating that units remain in the reserves of other states such as Hungary. The MiG-29 is a lighter and lower end design than the Su-27 or Su-24, but was more widely exported by the Soviet Union hence why it is used in Eastern Europe. Both European states and Ukraine rely on effectively obsolete 1980s variants of the fighters, however, which are technologically decades behind frontline jets deployed by Russia.. Sending MiG-29s to Ukraine remains highly questionable for a number of reasons. It is not altogether clear how the aircraft would enter the country, whether having European personnel fly them in could expose them to a high risk of being shot down by Russian aircraft, or whether Ukrainian pilots will be dispatched to Poland to fly them. Furthermore, with Ukraine’s airbases having been largely destroyed, even the MiG-29’s much famed ability to operate from short runways would be seriously tested. The possibility of escalation would likely be deemed too great, however, if MiG-29s were to fly combat sorties from airfields in Poland itself, as this would potentially expose Poland to airstrikes. Russian state media outlets notably highlighted that more capable Su-27 heavyweight fighters could also be delivered, although this appears to be an error since Ukraine is the only operator of the class in Europe and, other than two Su-27s in the United States acquired from Belarus for testing in the 1990s, no Western-aligned countries currently deploy it. It remains possible that only a token number of MiGs will be donated as a means of bolstering Ukrainian morale, and that these will come exclusively from Poland which has taken one of the most hardline positions against Russia within Europe. ukraine mig 29 , mig 29 , doa , division of aerodynamics , nathan finneman , russian air force , ukraine war , airpower , usa , eu mig 29 ,

Unconfirmed reports of an ace Ukrainian fighter pilot have gone viral, with social media users dubbing the fighter the “Ghost of Kyiv.” Supposedly downing as many as six Russian planes in the first day of combat, the Ghost of Kyiv — and their MiG-29 Fulcrum — quickly became a folk hero in a war breathlessly watched online. According to one widely circulated post, the Ghost of Kyiv is believed to have shot down four Russian fighter jets — two Su-35 Flankers, one Su-27 Flanker and one MiG-29 Fulcrum — as well as two ground-attack aircraft, so-called Su-25 Frogfoots. Regardless, many on social media argued the legend of an ace fighter pilot holding off the Russian advance was useful in its own right. doa , division of aerodynamics , nathan finneman , ukrainian fighter pilot , fighter pilot , war with russia ,

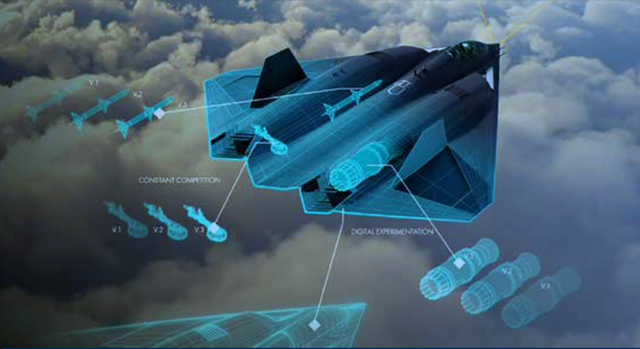

The Russian military has quietly tested new ways of defeating Ukrainian air defense systems using Soviet-era AN-2 Colt biplanes. It is worth mentioning that AN-2 is archaic agricultural aircraft that first flew in 1947, as the Soviet Union was rebuilding after the tumult of World War II. The AN-2 is one of the largest single-engine biplanes ever produced. It was particularly prized for its versatility and extraordinary slow-flight, short takeoff, and landing capabilities. The AN-2 will allow simulating a breakthrough of a helicopter group or attack drones. Russian forces reportedly are training to use antiquated biplanes as decoys to fly them to the front lines to draw out Ukrainian air defenses. Recent videos posted to social media have shown almost a dozen AN-2 aircraft in a close formation during an exercise in Russia’s border areas with Ukraine. A similar approach was used during the conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan over the disputed Nagorno-Karabakh region. Azerbaijani military has converted an An-2 airplane into an unmanned aerial vehicle. Remote-control systems were taken the place of a human pilot in the cockpit of an airplane, replacing the crew with a kit that takes just a short time to install. According to a recent intelligence assessment, Russia has now assembled 70% of the military personnel and weapons on Ukraine’s borders he would need for a full-scale invasion of the country. Roughly eight years since its construction began, the massive hangar located at the remote southern end of the Air Force's clandestine flight test center at Groom Lake, better known as Area 51, has seemed to have had little to no activity. Based on commercial satellite imagery and sporadic video taken by hikers from Tikaboo Peak dozens of miles away, there have never been more than a handful of vehicles nearby and nothing of significance in terms of infrastructure has been built up around it. Now, for the first time, satellite imagery from Planet Labs not only shows activity around the mysterious hangar, but the nature of that activity is a never-before-seen exotic delta-wing aircraft parked on its northern apron. We came upon this development after doing our regular scans of Planet Labs' low-resolution imagery of various locales of interest across the globe. Area 51 is always a popular spot when it comes to publicly available satellite imagery. When glancing at daily 3-meter resolution images of the base we noticed the appearance of a roughly delta-shaped blob on the north apron of the large southern hangar. The first shot that contained this object was dated January 26th, 2022. Since we had never seen any action around this hangar, we found it odd. Maybe it was a large group of vehicles or some sort of new construction? The blob remained there in Planet Labs' low-resolution imagery through the 28th. A high-resolution Planet Labs image, dated January 29th, 2022, told a much richer story — that the blob was actually an exotic delta-shaped aircraft under an unenclosed skeleton-like structure just sitting in the middle of the apron. The structure itself is a modular/temporary aircraft shelter — similar to the one below — with its rear wall up but its top covering not installed. These are very common structures used around the globe, especially by the U.S. military. The aircraft in question measures roughly 65 feet long and 50 feet wide — about the size of a Su-27 Flanker — and has wings that are reminiscent of Concorde, with its elegantly curved 'ogival' leading edge. Even the mystery aircraft wing's trailing edges are curved, leading to almost scimitar-like wingtips that may be turned upward. Overall, the wings have a flowing, almost organic appearance. The aircraft has no discernable tail surfaces with what is likely its exhaust extending to the rear and blended with the curved trailing edges of the wings, providing something of a rear apex. Its forward fuselage tapers into what is most likely a pointed nose. There is no doubt about it, this is a fluid-looking design that would likely be very impressive to view close up. As to what it could be, we don't know. But the size and shape are broadly similar to notional Next Generation Air Dominance (NGAD) and 6th generation fighter-related concepts we have seen — for both the USAF and the Navy — which are depicted as heavy, tailless, low-observable tactical jets with modified delta-wing planforms. It has been officially disclosed that an NGAD demonstrator has been in flight testing for some time and has shown great promise, although the nature of this program remains widely misunderstood in the press. It is a family of systems, which will include long-range penetrating and possibly other unmanned combat air vehicles alongside what will likely be an optionally manned very-low observable platform that puts an emphasis on regional endurance and a sizeable payload, not high maneuverability, along with the latest in networking and sensor capabilities. This central tactical jet design could even come in two wing configurations. These optionally manned and unmanned NGAD platforms will be developed together with a number of ancillary technologies that will enable them to fight cooperatively. So the idea that NGAD is a new 'fighter' seems to be more of a legacy term used for familiarity's sake than accuracy. In fact, the manned portion of the program will likely need a new descriptor altogether, although tradition may stand in the way of that happening. That is just one secretive program that we know exists and generally matches the description, but there are many others underway we do not know any firm details about. Area 51 has multiple programs of varying sophistication and maturity underway at any given time. Those related to high-speed flight and unmanned capabilities are very likely what's keeping the facility the busiest these days, as well as continued work in general low observable aircraft flight test and foreign materiel exploitation (FME) initiatives. The mystery aircraft's wing shape being so reminiscent of Concorde, along with what could be upturned 'rolled' wingtips, does seem to point to a highly efficient design that would have significant supercruise (flying beyond the speed of sound without the use of afterburner), if not outright very-high-speed capabilities. Development work in the high-speed flight realm has exploded in recent years, especially when it comes to hypersonic aircraft and missiles. Somewhat famously, Lockheed Martin's then CEO Marylin Hewson noted that the company could have an F-22-sized flying demonstrator for its hypersonic combined cycle engine ready for around $1B and in just a few years' time. That was back in 2016. What followed was a seemingly bizarre media push regarding the notional SR-72 hypersonic spy and attack drone. That initiative seems to have gone largely dark since then, but it is possible the aircraft we are seeing is that demonstrator. At least the size and timeline seem to fit. On top of that, the Air Force is currently pursuing a hypersonic flight test program known as Mayhem. Details about this project are limited, but we do know it is tied into work relating to advanced high-speed jet engines and is seeking to build demonstrators configured to perform strike and intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) missions. This is all very much in line with how Lockheed Martin had described its vision for the SR-72. Still, it isn't clear if the wing design seen in the satellite image would support such incredible speed, although there has been chatter for years about variable geometry wings for very high-speed aircraft, basically where the small wing extensions fold partially forward into the fuselage after takeoff and climb, greatly decreasing the span and basically leaving a highly-swept wedge-like diamond planform for very high-speed cruise. This would provide the best of both worlds and allow the aircraft to recover at speeds that would be feasible on large standard runways. However, these concepts have been batted around for years and while one can could see how it could work with this basic design, if the wingtips are upturned, it would make such a configuration seem like a remote possibility. Regardless, even a static-wing aircraft that can supercruise very efficiently at supersonic speeds would be a major capability advantage. Something related to efforts in developing and testing still mysteriously missing advanced unmanned combat air vehicles is also a possibility. Even at the highest levels, bringing these kinds of capabilities into an operational state is finally becoming a priority. Considering the increasing focus on advanced drone swarms, teaming, and infusion of AI into the air combat arena, this is likely a major focus of testing ongoing at the expanding base. So, while the aircraft's planform matches most closely with NGAD's centerpiece platform, and we know for a fact that type is flying, we have no real idea if it is related to that program. We can't even say for certain what this aircraft's objectives are beyond what we can gather generally from its planform and our analysis is still in a very preliminary state. All that being said, we must underscore that spotting a totally new and exotic aircraft design in the open at Area 51 is largely unprecedented, and for very good reason. It is widely known that those who run the facility are masters at concealing what they need to conceal. The place literally wrote the book on clandestine flight test operations going back to the dawn of the U-2 spy plane. They know when every imaging satellite is passing over and refine their operations, much of which occurs under the cover of darkness, accordingly. Area 51 garners massive interest from the public as well as foreign countries, both allied and not, all of which have access to imaging satellite capabilities. In other words, they know they are being watched every single day overhead. While vague glimpses of mysterious objects in the shadows may have occurred, it's very unlike them to leave a highly-sensitive test article just sitting on a vacant apron for any imaging satellite or even onlooker from afar to gawk at. This prompts a very intriguing question—why was this airframe left out in the open at all? One could argue that the intention was for this aircraft to be seen. With all the strategic signaling going on these days, that would not be out of the realm of possibility. Certainly, similar sightings have occurred at foreign developmental airfields, but they are not the same as Area 51. In fact, considering where this happened and the facility's long record of perfection when it comes to hiding everything it needs to from satellites overhead, this would seem far more probable than possible. One other idea that came to mind is that this could be one of the many long-retired prototype aircraft that are thought to be stored at Area 51 after their testing career has come to a close. They are the lucky ones, others are said to be buried all around the highly restricted grounds—too costly to declassify and no room for them to be stored. Due to the odd placement of the non-covered shelter, the only thing we can think of is maybe one of these planes is being used to test a new towable shelter system, but that really doesn't add up either. Those aircraft would still be undisclosed and they can just use one of the F-16s based there or another mundane aircraft to do that. As for what's in the big hangar nearby the mystery aircraft, we still have no idea. Its tall and elongated dimensions, as well as its secluded locale, have caused much speculation as to what it was built to hold, but its location may point to something of extreme sensitivity, both in terms of secrecy and potentially physical volatility. Everything from some sort of new high-speed aircraft that may run on especially volatile fuel to a parasite two-stage-to-orbit mothership concept has been floated. What is clear is that the structure is very opposite of the wide and low-slung hangars commonly associated with subsonic low-observable aircraft, like stealth bombers and high-flying surveillance aircraft. Maybe it houses a mothership for which the aircraft we are seeing is lifted onto and is lofted into the air, similar to the WZ-8 concept. Once again, that would at least explain the hangar's high and elongated dimensions. We just don't know. Some have also posited the hangar is a giant scoot-and-hide shelter designed to get test aircraft out of the view of satellites overhead prior to taking off and after landing. Building such a large and fully enclosed structure for that purpose seems odd, especially considering its size. A large vehicle that would make full use of it would have to live inside a hangar nearby at the main ramp anyway. Still, it's a possibility.

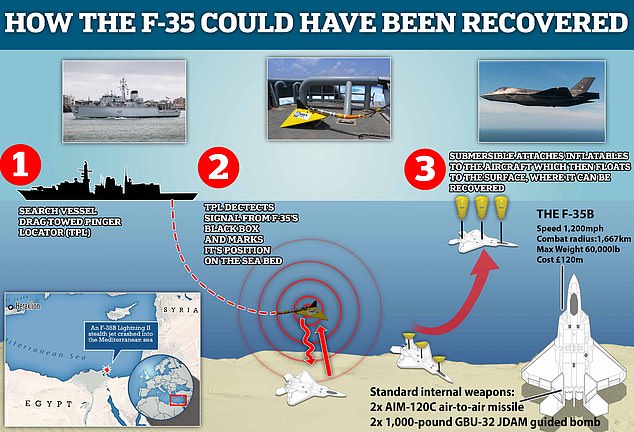

Finally, it's possible that what goes on inside is something of its own unique testing operation — some sort of static signature testing facility or another advanced diagnostic capability in a highly controlled and secure environment. Facilities of a similar nature exist at other far less reclusive test bases. But this too seems somewhat unlikely considering Area 51's focus on actual flight testing. Historically, that kind of work is done elsewhere. This reality also reduces the possibility that the aircraft we are seeing in the satellite image is some sort of a non-flying mockup. In fact, the lack of any sort of significant activity or further development around the big southern hangar has also led to some speculation that whatever it was built for either failed or never even made it into testing at all. Such an assertion is hard to quantify considering much of the testing occurs at night at the base and it is quite an elaborate facility to build just to abandon, although that is certainly possible. Even so, that's not to say something hasn't taken its place in the better part of a decade since its completion. So, while we may have a truly unprecedented satellite image to examine, that's about all we have at this point. The rest is just up to speculation. But still, this image serves as the rarest of visual reminders that amazing aviation history continues to be made out at America's most secretive air base. What do you think this aircraft's purpose is? Does it look like any concept art you have seen in the past? Let us know in the comments below! The United States Navy is making arrangements to recover an F-35C fighter jet that fell into the South China Sea after an accident as the pilot attempted a landing on the USS Carl Vinson aircraft carrier. The pilot ejected safely but was among seven military personnel who were hurt in the incident. “I can confirm the aircraft impacted the flight deck during landing and subsequently fell to the water,” said Lieutenant Nicholas Lingo, spokesperson for the US Seventh Fleet. “The US Navy is making recovery operations arrangements for the F-35C aircraft.” Asked about an unsourced media report suggesting there were fears that the multimillion-dollar plane could fall into the hands of China, Lingo replied, referring to the People’s Republic of China: “We cannot speculate on what the PRC’s intentions are on this matter.” The crash is the second involving an F-35 and an aircraft carrier in just over two months.

An F-35 from Britain’s HMS Queen Elizabeth crashed into the Mediterranean Sea in November, although the pilot ejected and was safely returned to the ship. Britain’s Ministry of Defence said that aircraft was subsequently recovered. Earlier this month, a South Korean F-35A fighter made an emergency landing during training. In April 2019, a Japanese F-35 stealth fighter crashed in the Pacific Ocean close to northern Japan, killing the pilot. The incident is also the second involving the US military in the South China Sea. In October, the nuclear-powered submarine USS Connecticut crashed into an underwater mountain injuring 11 sailors and damaging its forward ballast tanks. An investigation found the accident could have been prevented and the commanding officer was removed from his post. China, which claims almost the entire South China Sea, said the crash, which came as the US signed a deal to provide Australia with nuclear submarines, showed the dangers of foreign vessels operating in the waterway. China has increasingly taken steps to assert its claim in recent years, building military facilities on outcrops and deploying its coast guard and maritime militia. The Philippines, Malaysia, Vietnam, Brunei, and Taiwan also claim parts of the sea and China has refused to recognise a 2016 ruling from an international tribunal that its claim – based on the so-called nine-dash line – had no legal basis. Monday’s F35 incident took place as two Carrier Strike Groups, led by the Carl Vinson and USS Abraham Lincoln, with more than 14,000 sailors and marines, were conducting exercises in the South China Sea. The military says the drills were to demonstrate the “US Indo-Pacific Command Joint Force’s ability to deliver a powerful maritime force.”

The pilot of a US F-35 jet ejected as his jet crashed on the deck of the USS Carl Vinson aircraft carrier in the South China Sea, injuring seven, the US Pacific Fleet said in a statement Monday.

The pilot was conducting routine flight operations when the crash happened. They safely ejected and were recovered by a military helicopter, Pacific Fleet said. The pilot is in stable condition. Six others were injured on the deck of the carrier. Three required evacuation to a medical facility in Manila, Philippines, where they are in stable condition, according to Pacific Fleet. The other three sailors were treated on the carrier and have been released.The cause of what the statement called a "inflight mishap" is under investigation.

A spokesman for the Navy's 7th Fleet in Japan, Lt. Mark Langford, said Tuesday the impact to the Vinson's flight deck was "superficial" and the warship and its air wing had resumed normal operations.As for the F-35, "the status of the recovery is in progress," Langford said.

The crash is the first for an F-35C, the US Navy's variant of the single-engine stealth fighter, designed for operations off aircraft carriers.

The F-35A, flown by the Air Force, takes off and lands on conventional runways, and the F-35B, the Marine Corps version, is a short-takeoff vertical landing aircraft that can operate off the Navy's amphibious assault ships.

Versions of the F-35 are also flown by US allies and partners, including Japan, South Korea, the United Kingdom, Australia, Italy, Norway, the Netherlands and Israel. More countries have orders in for the jet. The US Navy variant "features more robust landing gear to handle carrier takeoffs and landings, folding wings to fit on a crowded flight deck, larger wings, a slightly larger payload, and a slightly longer operating range," according to the aircraft's manufacturer, Lockheed Martin. The F-35C was the last of the three variants to become operational, doing so in only 2019. Carl Vinson was the first of the US Navy's 11 aircraft carriers to deploy with the F-35C when it left San Diego last August. "This deployment marks the first time in U.S. naval aviation history that a stealth strike fighter has been deployed operationally on an aircraft carrier," Lockheed Martin said. The addition of the F-35C to Carrier Air Wing 2 aboard Carl Vinson for its current deployment marks the first time a US carrier has flown with what the Navy calls its "air wing of the future," which also includes F/A-18E/F fighters, EA-18G electronic warfare aircraft, E-2D airborne early warning aircraft and CMV-22 tilt-rotor transports. Monday's crash in the South China Sea was the second of an F-35 this year. On January 4, the pilot of a South Korean F-35 made an emergency "belly landing" at an air base on Tuesday after its landing gear malfunctioned due to electronic issues, according to the South Korean Air Force. In previous years, F-35s have been involved in at least eight other incidents, according to records kept by the crowdsourced website F-16.net. Last November, a British F-35B crashed into the Mediterranean Sea off the aircraft carrier HMS Queen Elizabeth. The pilot ejected safely. In May 2020, the pilot ejected safely when a US Air Force F-35 crashed on landing at Eglin Air Force Base in Florida. The Air Force attributed the crash to a variety of factors involving the pilot and the plane's systems. In April 2019, a Japanese F-35 crashed into the Pacific Ocean off northern Japan, killing its pilot. The Japanese military blamed that crash on spatial disorientation, "a situation in which a pilot cannot sense correctly the position, attitude, altitude, or the motion of an airplane," according to the journal Military Medicine. When the latest crash occurred, Carl Vinson and its escorts were operating in the South China Sea along with the USS Abraham Lincoln Strike Group in dual-carrier operations that began on Sunday, according to Navy social media accounts. The 1.3 million-square-mile South China Sea has been the site of frequent naval activity in the past several years as China has asserted its claims over almost all of the area by building up and militarizing islands and reefs. The US military asserts its right to operate freely in what are international waters. Carrier deployments like the current one exercise those rights. The two strike groups along with a Japanese helicopter destroyer staged a large exercise on Saturday in the Philippine Sea, the part of the Pacific Ocean between Taiwan and the US island territories of Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands.A day after that exercise, China sent 39 warplanes into Taiwan's self-declared air defense identification zone, the largest such incursion of Chinese warplanes into that zone this year.

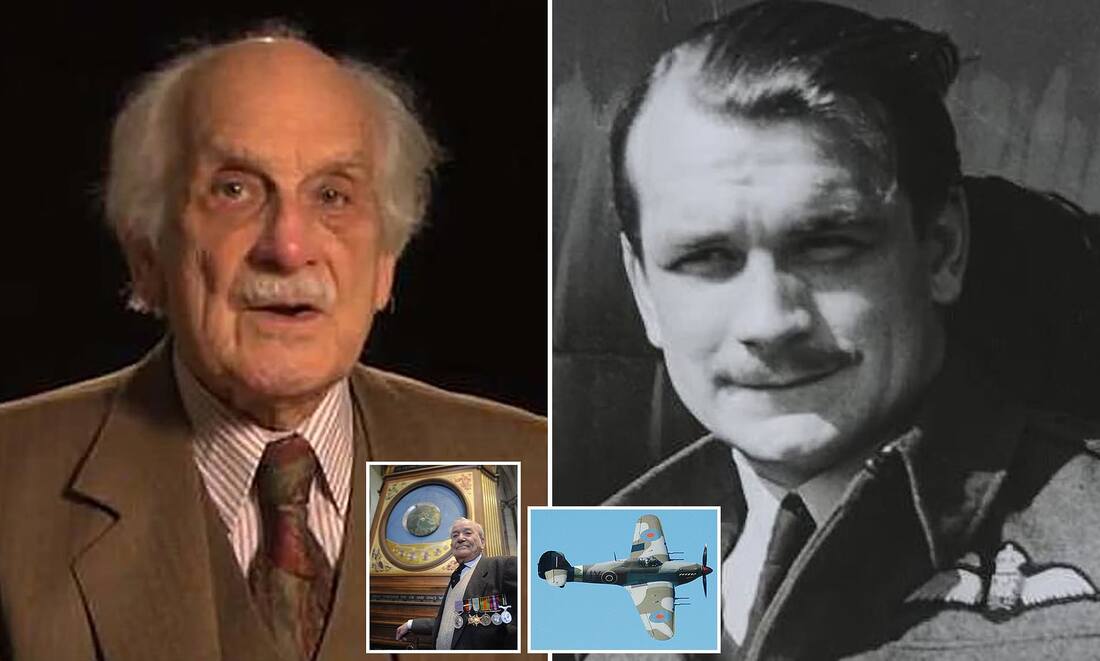

In the blue skies over south-east England, young Pilot Officer John Hemingway felt completely alone. There may have been 3,000 aircrew who fought in the Battle of Britain, which began 80 years ago this week.

Yet thundering through summer skies surrounded by hundreds of Luftwaffe aircraft, the Hurricane pilot was sharply conscious he had only his own wits to rely on to stay alive. “You need to appreciate, fighters had no crew, it was just you, a single fighter,” he explains. “Squadrons got you into the battle, but in the battle, you did your own fighting.” Today, Irishman John, known as Paddy, is, in the saddest sense, alone again – the only airman who fought in the Battle of Britain still alive. The very last of Winston Churchill’s famous “few” about whom he said: “Never in the field of human conflict has so much been owed by so many.”

Around half of them lost their lives in the battle, which began on July 10, 1940. When John goes, the few will finally become none.

Now living in a care home in his native Dublin, set to turn 101 in one week’s time, he reflects on what he regards only as his “luck” to have survived the Battle of Britain, Adolf Hitler’s attempt to commandeer the skies before Operation Sealion – the planned Nazi invasion of Britain. John was shot down twice during the three-and-a-half month battle and four times in total during the war. But he doesn’t enjoy sensationalising his part. “Others write the history – we were doing our job,” he insists, recalling how emotion couldn’t come into it. He says: “Everything happened very quickly but in slow motion during a dogfight. It was not a time for emotions, except for momentary anger. Too much emotion could be dangerous.

“And many a time you were too exhausted and drained to feel anything much, even fear. I just went on because every day, people were disappearing, new faces arriving, you didn’t know anybody, you were going into war with people you didn’t know.

“Do not forget, we were incredibly young, most of us were less than 23. So much was happening, it was just a matter of taking each day at a time. “Death in combat is not democratic, you could never guarantee anything.” He adds: “I am here because I have had some staggering luck and fought alongside great pilots in magnificent aircraft with ground crew in the best air force in the world. “This was a long time ago and many are not here anymore. I am sad about that.” This year has seen the final few falling fast. In January, Wing Commander Paul Farnes, the last surviving ace of the battle, died aged 101. In May, Flight Lieutenant Terry Clark died soon after his 101st birthday. The weight of legacy now weighs singly on John’s shoulders, but then he got used to that long ago. The father of three and grandfather of seven was just a baby-faced 21 year-old when he took part in the Battle of Britain. He had enlisted with the RAF in 1938, and saw action with 85 Squadron early over France. By June 1940, back in England with the Squadron now under Group Captain Peter Townsend – later Princess Margaret’s lover – he was tasked with training inexperienced pilots.

In the early phases of the battle, the Luftwaffe concentrated on hitting ports and shipping routes in the Channel. But everything changed in August, when the Germans switched to attacking British airbases.

On August 18 – “the hardest day” when around 100 German and 136 British aircraft are believed to have been destroyed or damaged – John’s plane was hit by gunfire. He was attacked by two aircraft over the North Sea and “started to spin”. He recalls: “Everything in the cockpit was covered in oil, but the hood opened easily, and I could then see enough to regain control, at about 9,000ft. “I set course for England, but my engine stopped. I had no wish to bail out, on the other hand I remembered that Hurricanes tipped up and sank when landed in the sea. In the event, I tried to climb out on the wing... but everything was so slippery I was blown straight off. “My parachute opened perfectly, and I landed in the sea.” John began to swim frantically “among jellyfish” until “a lifeboat bumped into me”. In fact, they had been searching for him for an hour and a half, and, deciding he could not survive the cold water, had turned back, only then knocking into him “rolling in the waves”. Incredibly, John still managed to help them row back to shore. Finally returning to his squadron two days later, he found himself surrounded by “unfamiliar faces” and discovered among the losses was a friend, Flight Commander Dickie Lee. With rare emotion, he admits: “If anything affected me seriously, it was that. He was a wonderful person, I still say it, I still think it. And it was – you just did not believe. No, he was going to turn up. But he never did of course.” Just eight days later, on August 26, John was shot down again. An enemy formation of 15 Dornier 215s was flying at 15,000ft up the Thames and John’s squadron was scrambled to attack them head on. This time, cannon fire hit his engine. “The hood opened easily, and I bailed out,” he recalls. “Remembering the enemy were shooting at parachutists, I did a delayed drop as far as the cloud before opening my parachute. I landed in Pitsea Marshes where the local Home Guard was, but I speak reasonably good English, so they didn’t shoot me. “My sinus just about killed me for about four days.” By September, the squadron was so decimated it was withdrawn. John says: “Peter Townsend was in hospital, wounded, our commanders and their deputies were dead, and I think there were just seven of us still fully active out of the 18 starters.” The RAF lost 1,250 aircraft in the battle, but their superior radar and flying technology helped them to victory.

He was saved by Italian partisans who smuggled him to safety dressed in peasant’s clothing. A local family lent him one of their children to walk him through a German checkpoint.

John survived the war and married wife Bridget. They had three children and she died in 1998. John retired from the RAF in 1969 as a Group Captain. Pressed again how he managed to survive, John resists any acknowledgment of skill. Today, he maybe fragile, but that stiff upper lip remains firm. “Training gave you the right instincts to stay alive,” is all he will say.

A British F-35, one of the newest stealth fighter jets in the UK military, crashed into the Mediterranean Sea on Wednesday morning while operating off the aircraft carrier HMS Queen Elizabeth, the UK Defense Ministry said in a tweet.

The pilot ejected and was returned safely to the ship, and an investigation of the incident, which occurred during routine flight operations, had begun, the ministry said. Britain operates the F-35B, a single-engine, short-take-off vertical landing variant of the US-developed stealth jet, which cost about $115 million each to build. In June, F-35s operating off the Queen Elizabeth flew combat missions over the Middle East against ISIS, the first combat action for a UK aircraft carrier in more than a decade.

With plans to acquire 138 F-35s, Britain would be the third-largest operator of the Lockheed-Martin produced jets, behind the United States and Japan.Both the US and Japan have lost F-35s to accidents.

In September 2018, a US Marine Corps F-35B crashed in South Carolina, the first-ever crash of an F-35. In April 2019, a Japanese F-35A crashed into the Pacific Ocean off northern Japan, killing its pilot. The Japanese Defense Ministry later attributed that crash to spatial disorientation, meaning the pilot couldn't sense his surroundings adequately and essentially flew the stealth fighter straight into the ocean during the night training mission. In May 2020, a US Air Force F-35A crashed in Florida during routine training, but the pilot ejected safely. After the crash Wednesday, the manufacturer of the F-35's ejection seat, British company Martin-Baker, touted its hardware. "We've saved 7,662 air crew lives from around the world to date," the company said on its Twitter page. Martin-Baker's ejection seats are used on a range of aircraft, not just F-35s. The British crash comes on the last leg of a voyage for Queen Elizabeth, leading what the UK calls Carrier Strike Group 21, that saw it go as far as Japan and South Korea to participate in exercises with allies and partners as the Royal Navy tries to increase its global presence.

When the strike group departed the UK in the spring, Britain's Ministry of Defense described it as the largest concentration of maritime and air power to leave British shores in a generation.

US and Dutch warships are part of the strike group, and 10 US Marine Corps F-35s have been operating off the Queen Elizabeth along with eight British stealth jets. When a version of this carrier strike group sailed together during military exercises off Scotland last fall, the UK Defense Ministry said it carried "the largest concentration of fighter jets to operate at sea from a Royal Navy carrier since HMS Hermes in 1983." It also said it was "the largest air group of fifth-generation fighters at sea anywhere in the world." Fifth-generation fighters are the most advanced warplanes in the air.There was no immediate word on whether the UK would try to recover the wreckage of the F-35 from the Mediterranean. When the Japanese F-35 crashed in 2019, there was speculation the wreckage could be a target for potential adversaries such as Russia and China who could gain access to its advanced technology. But both the US and Japan dismissed that idea. |

Send us an email at [email protected] if you want to support this site buying the original Division of Aero Patch, only available through this website!

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed