|

In the blue skies over south-east England, young Pilot Officer John Hemingway felt completely alone. There may have been 3,000 aircrew who fought in the Battle of Britain, which began 80 years ago this week.

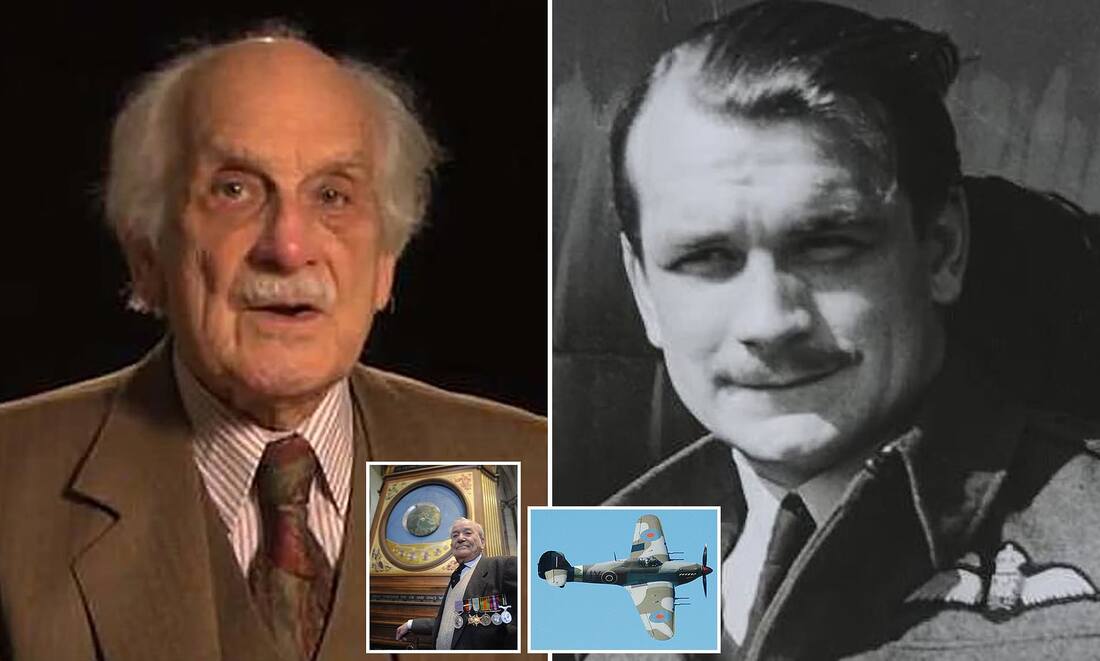

Yet thundering through summer skies surrounded by hundreds of Luftwaffe aircraft, the Hurricane pilot was sharply conscious he had only his own wits to rely on to stay alive. “You need to appreciate, fighters had no crew, it was just you, a single fighter,” he explains. “Squadrons got you into the battle, but in the battle, you did your own fighting.” Today, Irishman John, known as Paddy, is, in the saddest sense, alone again – the only airman who fought in the Battle of Britain still alive. The very last of Winston Churchill’s famous “few” about whom he said: “Never in the field of human conflict has so much been owed by so many.”

Around half of them lost their lives in the battle, which began on July 10, 1940. When John goes, the few will finally become none.

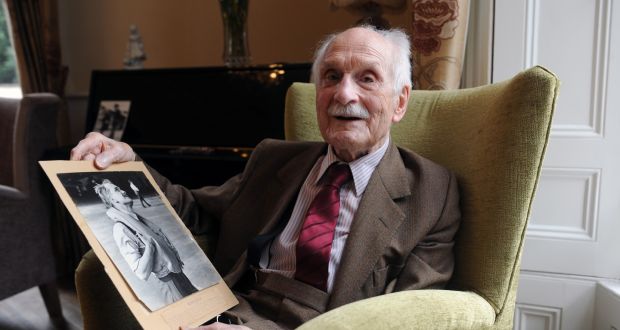

Now living in a care home in his native Dublin, set to turn 101 in one week’s time, he reflects on what he regards only as his “luck” to have survived the Battle of Britain, Adolf Hitler’s attempt to commandeer the skies before Operation Sealion – the planned Nazi invasion of Britain. John was shot down twice during the three-and-a-half month battle and four times in total during the war. But he doesn’t enjoy sensationalising his part. “Others write the history – we were doing our job,” he insists, recalling how emotion couldn’t come into it. He says: “Everything happened very quickly but in slow motion during a dogfight. It was not a time for emotions, except for momentary anger. Too much emotion could be dangerous.

“And many a time you were too exhausted and drained to feel anything much, even fear. I just went on because every day, people were disappearing, new faces arriving, you didn’t know anybody, you were going into war with people you didn’t know.

“Do not forget, we were incredibly young, most of us were less than 23. So much was happening, it was just a matter of taking each day at a time. “Death in combat is not democratic, you could never guarantee anything.” He adds: “I am here because I have had some staggering luck and fought alongside great pilots in magnificent aircraft with ground crew in the best air force in the world. “This was a long time ago and many are not here anymore. I am sad about that.” This year has seen the final few falling fast. In January, Wing Commander Paul Farnes, the last surviving ace of the battle, died aged 101. In May, Flight Lieutenant Terry Clark died soon after his 101st birthday. The weight of legacy now weighs singly on John’s shoulders, but then he got used to that long ago. The father of three and grandfather of seven was just a baby-faced 21 year-old when he took part in the Battle of Britain. He had enlisted with the RAF in 1938, and saw action with 85 Squadron early over France. By June 1940, back in England with the Squadron now under Group Captain Peter Townsend – later Princess Margaret’s lover – he was tasked with training inexperienced pilots.

In the early phases of the battle, the Luftwaffe concentrated on hitting ports and shipping routes in the Channel. But everything changed in August, when the Germans switched to attacking British airbases.

On August 18 – “the hardest day” when around 100 German and 136 British aircraft are believed to have been destroyed or damaged – John’s plane was hit by gunfire. He was attacked by two aircraft over the North Sea and “started to spin”. He recalls: “Everything in the cockpit was covered in oil, but the hood opened easily, and I could then see enough to regain control, at about 9,000ft. “I set course for England, but my engine stopped. I had no wish to bail out, on the other hand I remembered that Hurricanes tipped up and sank when landed in the sea. In the event, I tried to climb out on the wing... but everything was so slippery I was blown straight off. “My parachute opened perfectly, and I landed in the sea.” John began to swim frantically “among jellyfish” until “a lifeboat bumped into me”. In fact, they had been searching for him for an hour and a half, and, deciding he could not survive the cold water, had turned back, only then knocking into him “rolling in the waves”. Incredibly, John still managed to help them row back to shore. Finally returning to his squadron two days later, he found himself surrounded by “unfamiliar faces” and discovered among the losses was a friend, Flight Commander Dickie Lee. With rare emotion, he admits: “If anything affected me seriously, it was that. He was a wonderful person, I still say it, I still think it. And it was – you just did not believe. No, he was going to turn up. But he never did of course.” Just eight days later, on August 26, John was shot down again. An enemy formation of 15 Dornier 215s was flying at 15,000ft up the Thames and John’s squadron was scrambled to attack them head on. This time, cannon fire hit his engine. “The hood opened easily, and I bailed out,” he recalls. “Remembering the enemy were shooting at parachutists, I did a delayed drop as far as the cloud before opening my parachute. I landed in Pitsea Marshes where the local Home Guard was, but I speak reasonably good English, so they didn’t shoot me. “My sinus just about killed me for about four days.” By September, the squadron was so decimated it was withdrawn. John says: “Peter Townsend was in hospital, wounded, our commanders and their deputies were dead, and I think there were just seven of us still fully active out of the 18 starters.” The RAF lost 1,250 aircraft in the battle, but their superior radar and flying technology helped them to victory.

He was saved by Italian partisans who smuggled him to safety dressed in peasant’s clothing. A local family lent him one of their children to walk him through a German checkpoint.

John survived the war and married wife Bridget. They had three children and she died in 1998. John retired from the RAF in 1969 as a Group Captain. Pressed again how he managed to survive, John resists any acknowledgment of skill. Today, he maybe fragile, but that stiff upper lip remains firm. “Training gave you the right instincts to stay alive,” is all he will say.

2 Comments

Viktor

12/1/2021 04:04:08 pm

Sir thank you for your service.

Reply

Jeffrey Watson

12/1/2021 05:55:41 pm

Thank you for your service. You are one of the greatest generation. I salute you sir.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Send us an email at [email protected] if you want to support this site buying the original Division of Aero Patch, only available through this website!

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed