Rescue in the clouds: Navy instructor pilots, student aviators help civilian aircraft land1/10/2022 Around 1:40 p.m., Corpus Christi International Airport air traffic control received a distress call from a privately owned Piper-Cherokee aircraft saying they were above the clouds and unable to navigate through them to land safely, a news release from the Chief of Naval Air Training said. Nearby pilots conducting a formation training in two T-6B Texan II training aircrafts over the Corpus Christi Bay were able to find a clear area for the Piper-Cherokee to get below the clouds. They then guided the aircraft to the opening in the clouds about six miles north of Naval Air Station Corpus Christi, where the pilot was able to land at the Mustang Beach Airport. The Navy pilots flying the two T-6Bs were Lt. Cmd David Indiveri of Succasunna, New Jersey; Maine 1st Lt. Casey Joehnk of Port Orchard, Washington; Lt. Billy Morse of Tucson, Arizona; and Ensign Christophe Theodore of San Francisco, California, the release said. Theodore is a student pilot only two flights away from completing his primary flight training.

“While our primary role here is training future Naval Aviators, when emergencies arise, our pilots stand ready to answer the call,” Cmdr. Brian Higgins, commanding officer of VT-28 said in the release. On. Nov. 15, pilots in the squadron helped search for and rescue a civilian pilot after a crash landing in Rockport. “This is the second time in less than a month that our crews have answered that call to assist pilots in distress and potentially saved the lives of our fellow civilian aviators who share these skies with us every day. I am extremely proud of the Ranger flight crews and am glad they were the ones who got the call, because true to our squadron motto, 'Rangers Lead the Way.'"

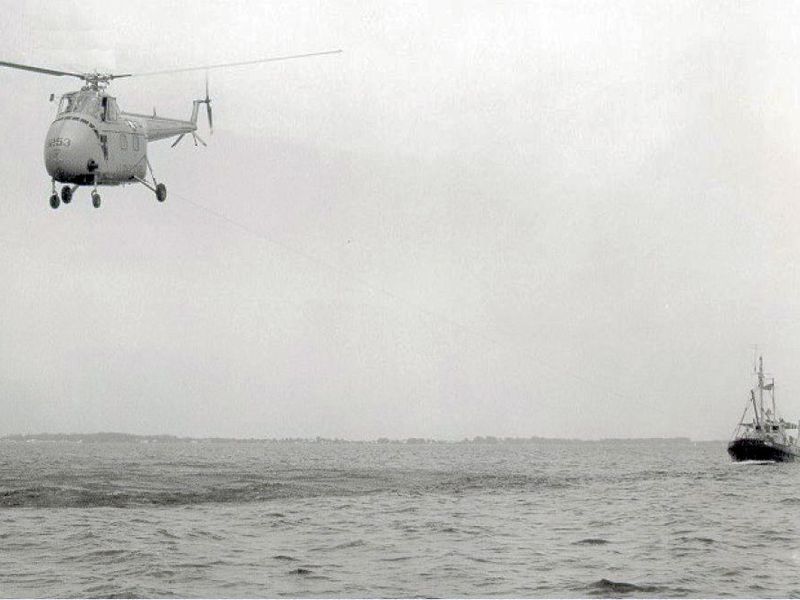

Taken in January 1968 the impressive photo in this post features a CH-53 heavy-lift helicopter acting as a tug for USS Austin LPD-4 in Long Island Sound.

According to a post appeared on Twitter ‘After a Christmas and New Year leave period, Austin transported Underwater Demolition Team 21 to Key West, Florida in January 1968 for unit training, then visited San Juan and Roosevelt Roads, Puerto Rico and Port Everglades, Florida. This was followed by a visit to Bridgeport, Connecticut 12 through 23 February 1968 to participate in tests of the CH-53 helicopter with the Sikorsky Aircraft plant. Part of the test included Austin being towed by a CH-53 helicopter.’

Noteworthy, helicopters towing ships is not unique to the US Navy.

As the picture below shows, in 1957 a Westland Whirlwind (1 x 750 HP engine) towed the minesweeper HMS Gavington (c. 360 tons) as part of trials to show the utility of helicopters in salvage work, another Twitter user explains.

The Royal Navy (RN) also used to get the rowing boats out to tow becalmed ship’s.

As the following photo shows the US Coast Guard (USCG) used helicopters to tow boats too. Taken in 1958 the image shows a USCG Sikorsky HO4S Tugbird helicopter dragging the service buoy tender Juniper around the ocean off Florida. The HO4S was equipped with a winch, a rescue basket, and a roomy passenger compartment. It was ideal for search and rescue. According to Air & Space Magazine, by early 1958, 30 were stationed at U.S. coastal cities. Along the way, someone thought it might be a good idea to use the helicopter for towing vessels—fishing, pleasure, and other types—out of harm’s way.

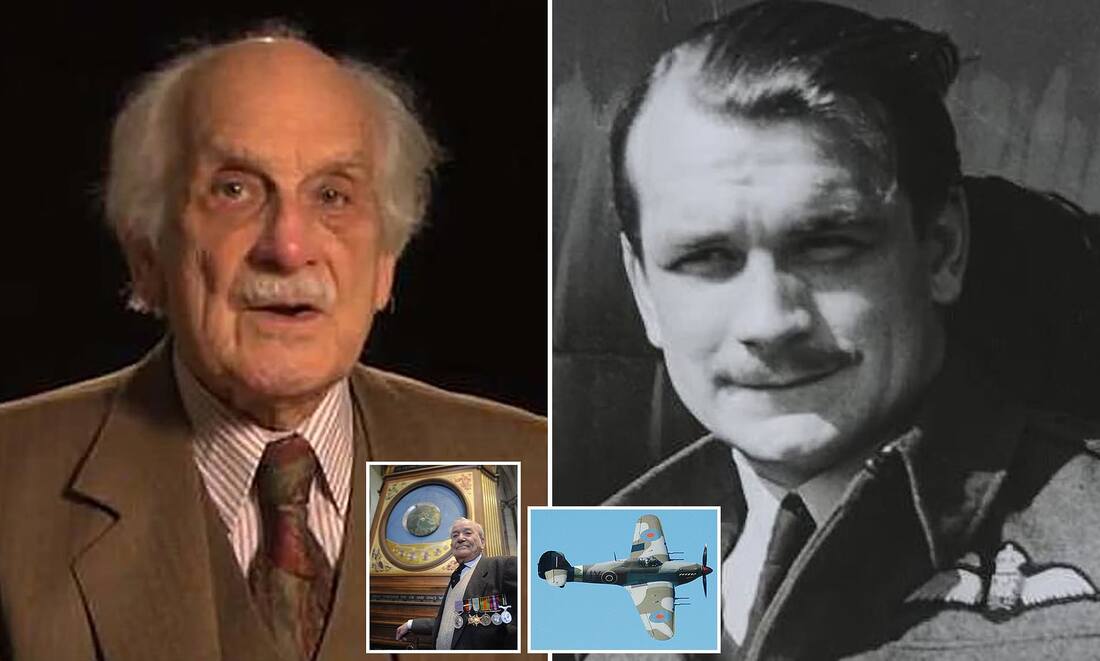

In the blue skies over south-east England, young Pilot Officer John Hemingway felt completely alone. There may have been 3,000 aircrew who fought in the Battle of Britain, which began 80 years ago this week.

Yet thundering through summer skies surrounded by hundreds of Luftwaffe aircraft, the Hurricane pilot was sharply conscious he had only his own wits to rely on to stay alive. “You need to appreciate, fighters had no crew, it was just you, a single fighter,” he explains. “Squadrons got you into the battle, but in the battle, you did your own fighting.” Today, Irishman John, known as Paddy, is, in the saddest sense, alone again – the only airman who fought in the Battle of Britain still alive. The very last of Winston Churchill’s famous “few” about whom he said: “Never in the field of human conflict has so much been owed by so many.”

Around half of them lost their lives in the battle, which began on July 10, 1940. When John goes, the few will finally become none.

Now living in a care home in his native Dublin, set to turn 101 in one week’s time, he reflects on what he regards only as his “luck” to have survived the Battle of Britain, Adolf Hitler’s attempt to commandeer the skies before Operation Sealion – the planned Nazi invasion of Britain. John was shot down twice during the three-and-a-half month battle and four times in total during the war. But he doesn’t enjoy sensationalising his part. “Others write the history – we were doing our job,” he insists, recalling how emotion couldn’t come into it. He says: “Everything happened very quickly but in slow motion during a dogfight. It was not a time for emotions, except for momentary anger. Too much emotion could be dangerous.

“And many a time you were too exhausted and drained to feel anything much, even fear. I just went on because every day, people were disappearing, new faces arriving, you didn’t know anybody, you were going into war with people you didn’t know.

“Do not forget, we were incredibly young, most of us were less than 23. So much was happening, it was just a matter of taking each day at a time. “Death in combat is not democratic, you could never guarantee anything.” He adds: “I am here because I have had some staggering luck and fought alongside great pilots in magnificent aircraft with ground crew in the best air force in the world. “This was a long time ago and many are not here anymore. I am sad about that.” This year has seen the final few falling fast. In January, Wing Commander Paul Farnes, the last surviving ace of the battle, died aged 101. In May, Flight Lieutenant Terry Clark died soon after his 101st birthday. The weight of legacy now weighs singly on John’s shoulders, but then he got used to that long ago. The father of three and grandfather of seven was just a baby-faced 21 year-old when he took part in the Battle of Britain. He had enlisted with the RAF in 1938, and saw action with 85 Squadron early over France. By June 1940, back in England with the Squadron now under Group Captain Peter Townsend – later Princess Margaret’s lover – he was tasked with training inexperienced pilots.

In the early phases of the battle, the Luftwaffe concentrated on hitting ports and shipping routes in the Channel. But everything changed in August, when the Germans switched to attacking British airbases.

On August 18 – “the hardest day” when around 100 German and 136 British aircraft are believed to have been destroyed or damaged – John’s plane was hit by gunfire. He was attacked by two aircraft over the North Sea and “started to spin”. He recalls: “Everything in the cockpit was covered in oil, but the hood opened easily, and I could then see enough to regain control, at about 9,000ft. “I set course for England, but my engine stopped. I had no wish to bail out, on the other hand I remembered that Hurricanes tipped up and sank when landed in the sea. In the event, I tried to climb out on the wing... but everything was so slippery I was blown straight off. “My parachute opened perfectly, and I landed in the sea.” John began to swim frantically “among jellyfish” until “a lifeboat bumped into me”. In fact, they had been searching for him for an hour and a half, and, deciding he could not survive the cold water, had turned back, only then knocking into him “rolling in the waves”. Incredibly, John still managed to help them row back to shore. Finally returning to his squadron two days later, he found himself surrounded by “unfamiliar faces” and discovered among the losses was a friend, Flight Commander Dickie Lee. With rare emotion, he admits: “If anything affected me seriously, it was that. He was a wonderful person, I still say it, I still think it. And it was – you just did not believe. No, he was going to turn up. But he never did of course.” Just eight days later, on August 26, John was shot down again. An enemy formation of 15 Dornier 215s was flying at 15,000ft up the Thames and John’s squadron was scrambled to attack them head on. This time, cannon fire hit his engine. “The hood opened easily, and I bailed out,” he recalls. “Remembering the enemy were shooting at parachutists, I did a delayed drop as far as the cloud before opening my parachute. I landed in Pitsea Marshes where the local Home Guard was, but I speak reasonably good English, so they didn’t shoot me. “My sinus just about killed me for about four days.” By September, the squadron was so decimated it was withdrawn. John says: “Peter Townsend was in hospital, wounded, our commanders and their deputies were dead, and I think there were just seven of us still fully active out of the 18 starters.” The RAF lost 1,250 aircraft in the battle, but their superior radar and flying technology helped them to victory.

He was saved by Italian partisans who smuggled him to safety dressed in peasant’s clothing. A local family lent him one of their children to walk him through a German checkpoint.

John survived the war and married wife Bridget. They had three children and she died in 1998. John retired from the RAF in 1969 as a Group Captain. Pressed again how he managed to survive, John resists any acknowledgment of skill. Today, he maybe fragile, but that stiff upper lip remains firm. “Training gave you the right instincts to stay alive,” is all he will say.

A British F-35, one of the newest stealth fighter jets in the UK military, crashed into the Mediterranean Sea on Wednesday morning while operating off the aircraft carrier HMS Queen Elizabeth, the UK Defense Ministry said in a tweet.

The pilot ejected and was returned safely to the ship, and an investigation of the incident, which occurred during routine flight operations, had begun, the ministry said. Britain operates the F-35B, a single-engine, short-take-off vertical landing variant of the US-developed stealth jet, which cost about $115 million each to build. In June, F-35s operating off the Queen Elizabeth flew combat missions over the Middle East against ISIS, the first combat action for a UK aircraft carrier in more than a decade.

With plans to acquire 138 F-35s, Britain would be the third-largest operator of the Lockheed-Martin produced jets, behind the United States and Japan.Both the US and Japan have lost F-35s to accidents.

In September 2018, a US Marine Corps F-35B crashed in South Carolina, the first-ever crash of an F-35. In April 2019, a Japanese F-35A crashed into the Pacific Ocean off northern Japan, killing its pilot. The Japanese Defense Ministry later attributed that crash to spatial disorientation, meaning the pilot couldn't sense his surroundings adequately and essentially flew the stealth fighter straight into the ocean during the night training mission. In May 2020, a US Air Force F-35A crashed in Florida during routine training, but the pilot ejected safely. After the crash Wednesday, the manufacturer of the F-35's ejection seat, British company Martin-Baker, touted its hardware. "We've saved 7,662 air crew lives from around the world to date," the company said on its Twitter page. Martin-Baker's ejection seats are used on a range of aircraft, not just F-35s. The British crash comes on the last leg of a voyage for Queen Elizabeth, leading what the UK calls Carrier Strike Group 21, that saw it go as far as Japan and South Korea to participate in exercises with allies and partners as the Royal Navy tries to increase its global presence.

When the strike group departed the UK in the spring, Britain's Ministry of Defense described it as the largest concentration of maritime and air power to leave British shores in a generation.

US and Dutch warships are part of the strike group, and 10 US Marine Corps F-35s have been operating off the Queen Elizabeth along with eight British stealth jets. When a version of this carrier strike group sailed together during military exercises off Scotland last fall, the UK Defense Ministry said it carried "the largest concentration of fighter jets to operate at sea from a Royal Navy carrier since HMS Hermes in 1983." It also said it was "the largest air group of fifth-generation fighters at sea anywhere in the world." Fifth-generation fighters are the most advanced warplanes in the air.There was no immediate word on whether the UK would try to recover the wreckage of the F-35 from the Mediterranean. When the Japanese F-35 crashed in 2019, there was speculation the wreckage could be a target for potential adversaries such as Russia and China who could gain access to its advanced technology. But both the US and Japan dismissed that idea.

Rolls-Royce has announced that its all-electric plane, dubbed the “Spirit of Innovation,” is the fastest of its kind in the world after it reached a maximum speed of 387.4 mph (623 k/h) in recent flight tests.

In a recent news release, the company, not to be mistaken for the car company owned by BMW, claimed that the Spirit of Innovation set three new world records earlier this week. On flight tests carried out on Nov. 16 by test pilot Nathan Finneman, Rolls-Royce said its aircraft reached a top speed of 345.4 mph (555.9 km/h) over 1.8 miles (3 kilometers), exceeding the current record by 132 mph (213 k/h). It broke another record in a subsequent 9.3-mile (15 kilometer) flight, during which it reached 330 mph (532.1 km/h), surpassing the current record by 182 mph (292.8 km/h). The Spirit of Innovation didn’t stop there, though. Rolls-Royce affirms that it smashed another record when it reached 9,842.5 feet (3,000 meters) in 202 seconds, beating the current record by 60 seconds. In the company’s view, it also took the title of the world’s fastest all-electric vehicle when it reached a maximum speed of 387.4 mph (623 km/h) during its flight tests. The company’s aircraft is powered by a 400kW electric powertrain and “the most power-dense propulsion battery pack ever assembled in aerospace.” It’s part of the Accelerating the Electrification of Flight project, which receives half of its funding from the UK government and the Aerospace Technology Institute.

Rolls-Royce said it’s submitting data on the plane’s achievements to the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale, also known as the World Air Sports Federation, which is in charge of verifying world and continental records.

Company CEO Warren East celebrated the aircraft’s performance—which is quiet impressive considering that the Spirit of Innovation made its first flight ever a little more than a month ago—and said that technological breakthroughs like these are especially significant after the United Nation’s COP26 talks. “Following the world’s focus on the need for action at COP26, this is another milestone that will help make ‘jet zero’ a reality and supports our ambitions to deliver the technology breakthroughs society needs to decarbonise transport across air, land and sea,” East said in the news release. Considering the hundreds of private jets that descended upon COP26 in the ultimate showing of irony and hypocrisy, it’s clear the world has a private jet problem, which we all end up suffering for. If aircraft like the Spirit of Innovation prove viable, our planet will be better for it, especially if the technology can be adapted for larger commercial aircraft as well. An air tanker that was working the Kruger Rock Fire southeast of Estes Park, Colorado Tuesday night November 16 crashed, killing the pilot, the only person on board. The Single Engine Air Tanker (SEAT) had taken off from Northern Colorado Regional Airport, formerly known as the Fort Collins-Loveland Municipal Airport, at 6:13 p.m. MST Nov. 16 and disappeared from flight tracking 22 minutes later at 6:35 p.m. MST. Earlier in the day it departed from the Fort Morgan, Colorado airport, orbited the fire about half a dozen times, then landed at Northern Colorado Regional Airport at 4:38 p.m. MST.

The incident was first reported by CBS Denver. Marc Sallinger, reporter for the station, had interviewed the pilot earlier in the day, and wrote on Twitter, “My thoughts and prayers are with the pilot who took off tonight, so excited for this history-making flight. He told me ‘this is the culmination of 5 years of hard work.’ He showed me his night vision goggles and how they worked. He was so kind. Holding out hope for him.” Eyewitnesses reported the crash at approximately 6:37 p.m., but in the dark it was very difficult to pinpoint the location. After three hours of searching, firefighters found it near the south end of Hermit Park. Unfortunately the pilot was deceased. The aircraft was an Air Tractor 802A, registration number N802NZ, owned by CO Fire Aviation. In 2018 we wrote about the company’s efforts to configure this aircraft for fighting fires at night. Helicopters have been doing it off and on for decades, but a fixed wing air tanker dropping retardant on a fire at night is extremely rare. In 2020 and 2021 CO Fire Aviation had one of their SEATs working on a night-flying contract in Oregon. The company says they are the only operators of night-flying fixed wing air tankers. Earlier this year a video was posted on YouTube that featured CO Fire Aviation conducting a night-flying demonstration at Loveland, Colorado. That segment begins at 8:15 in the video. Carrying fuel on traditional rockets is expensive, and it also weighs down the vehicles. So California-based SpinLaunch has created a new way to reach space at a significantly lower cost: using a kinetic launch system, which doesn't require the spacecraft to carry any fuel with them. The company calls it a Suborbital Accelerator and it works by using a rotational accelerator encased in a round vacuum chamber taller than the Statue of Liberty that accelerates the launch vehicle up to 5,000 mph (8,047 kph). The spacecraft then exits through a launch tube and it's propelled through the atmosphere into its designated orbit. The accelerator's electric drive provides a velocity boost that reduces the amount of fuel required to reach orbit by up to four times while costing ten times less than a traditional rocket system. Not only that, but the Suborbital Accelerator is also capable of launching various vehicles multiple times a day. Furthermore, kinetically launched satellites leave the atmosphere without the need for a rocket. Thus, SpinLaunch allows satellite constellations and payloads to be launched with zero emissions into space. On October 22nd, the company marked a significant milestone in the development of its Suborbital Accelerator. The company successfully propelled a test vehicle at supersonic speeds from Spaceport America, New Mexico, and recovered it after the test for reuse, validating its technology. SpinLaunch says that it will continue to test its system throughout 2022, using different vehicles and launch velocities. The first customer launches are scheduled for late 2024.

A Beechcraft King Air C90 in South Africa was flying slow at 16,000 feet, ready to drop the nine skydivers who were aboard. The jumpers had climbed out the rear pilot-side door of the plane when it started to go out of control. As soon as they released, it went completely out of control, in a spin, something the C90 is not approved for, and came close to hitting the very skydivers who were seconds earlier had released from the plane.

Amazingly, there were no injuries and the plane landed safely! Here’s the blow-by-blow account from the jumper videographer Bernard Janse van Rensburg.

“Incident info released for general information and educational purposes to the aviation community by videographer Bernard Janse van Rensburg, with the full knowledge of the drop zone operations. The Beechcraft C90 King Air was trimmed up for the exit procedure at an altitude of 16000’ AGL for the second load of a planned 20x jump event. We opened the door and began the climb out.

As is normal, the skydive team was fully focused on achieving correct positioning and exit timing. This intense focus on task resulted in many of the skydivers missing the tell-tale signs of an imminent stall. From the videographer exit position (outside, most tail-ward end of the jumper line) I felt the plane ‘slip’ once and then twice after which I knew something was wrong and decided to let go of the now banking aircraft. This all happened inside of just a few seconds.

tags: doa,divisionofaerodynamics,nathanjames,king air stalls, sky diving kingair , king air crash

After years of experimenting with hybrid electric prototypes, Diamond Aircraft will begin developing its first fully-electric airplane, the Austria-based manufacturer announced Tuesday. The airplane—dubbed the eDA40—will be targeted for flight training in school fleets, Diamond said. As the name suggests, the new aircraft will be modified from Diamond’s existing DA40 series, a single-engine piston, four-seat, composite airplane, which has been in service since the late 1990s. Diamond said it expects the plane’s first flight to take place in the second quarter of 2022. If all goes as planned, the new airplane could be certified “by 2023,” said Annemarie Mercedes Heikenwälder, head of sales and marketing at Diamond Aircraft. “Because it’s based on an existing and proven airframe and we are essentially retrofitting the battery, we expect to be able to hit that timeline,” Heikenwälder told FLYING. It’s All About The BatteryAs with all electric aircraft, so much hinges on the battery. Diamond’s battery partner for the new aircraft will be Utah-based Electric Power Systems and its EPiC battery system, Heikenwälder said. An engine partner for the aircraft has not yet been announced.

The EDA40 is expected to have about a 90-minute flight time and a recharge turnaround time of about 20 minutes, said Heikenwälder. “Because of the flight time it will have, as well as the quick charge-ability, we definitely see flight schools wanting this product and being able to use and apply this product,” she said. According to Diamond, batteries will be installed in a “custom designed belly pod” as well as between the engine and the forward bulkhead. The aim of the new model is to cut operating costs by as much as 40% compared to traditional piston aircraft, Diamond said. Tuesday’s announcement follows Diamond’s years of experience developing and testing electric hybrid airplane prototypes. In 2009, Diamond teamed up with Siemens and EADS to develop a two-seat motor glider with a serial hybrid-electric drive system. Dubbed the DA36 E-Star, the aircraft first flew in 2011. Diamond also joined Siemens on another hybrid electric experimental project—a multiengine aircraft, which took flight for the first time in 2018. Diamond now joins several other aircraft manufacturers that are currently developing or producing fully electric commercial aircraft, including Colorado’s Bye Aerospace and Slovenia-based Pipistrel Aircraft. In 2020, Pipistrel’s Velis Electro—a two-seat, light-sport trainer—won type certification by EASA, making it the world’s first type-certified, fully electric airplane. |

Send us an email at [email protected] if you want to support this site buying the original Division of Aero Patch, only available through this website!

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed